Tell us something about your background and how your interest in travel developed.

My parents were Czechoslovak citizens; Dad was born in 1902 near Brno, Moravia at a time when Czechoslovakia was not yet a nation but part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Mum was born in Haifa, Palestine in 1918 and met my father when he was travelling as a store controller in Lebanon, Syria and the British Mandate for Palestine, working for the Bata Shoe Company of Zlín, Czechoslovakia. I was made in Czechoslovakia the same week that Hitler annexed the Czech lands of Bohemia and Moravia to create Nazi Germany’s Protektorat Böhmen und Mähren.

As an unborn fetus, I “travelled” through eleven countries when my father and pregnant mother left Zlín and journeyed by train and Italian cargo ship (Trieste to Mombasa, via the Suez Canal) to reach Nairobi, Kenya, where I was born. Many of these eleven lands were visited later when I became an independent traveller; some no longer exist. Such multicultural stirrings in the womb—fetal origins, if you will—must have left an indelible mark on my psyche and seeded a powerful inclination to travel widely.

We spent the war years in British East Africa until I was seven, before Bata Shoe, seeking fresh markets in the Middle East, dispatched our family to Tehran. Getting to Iran meant flying from Nairobi to Cairo, via Khartoum—a two-day journey on a 3-engined Junkers Ju 52 monoplane. It was a German Luftwaffe troop transport captured by the RAF in North Africa and refitted for passenger service. We then took the train from Cairo, crossing the Suez Canal and the Sinai, past Gaza, and on to Palestine. From there, it was by bus to Lebanon, a flight to Baghdad and thereafter to Tehran. How far away, Iran’s capital city seemed from the British Empire and its Crown Colony of Kenya. I still recall the culture shock I felt as a seven-year-old whose sensibilities were shaken by the primitive conditions in a dismayingly backward, post-war Iran.

But Iran would soon leap into the 20th century, thanks to the black magic of petroleum, a progressive Shah, a tolerant society open to many faiths and receptive to foreign ideas and Western technological expertise. The country’s infrastructure modernised rapidly during the 1960s and I adapted to the speed of the changes in my new homeland.

With the global repositioning taken care of, we next got sucked into a political whirlpool. Propped up by the Soviet Union, a 1948 coup d’état in Czechoslovakia brought four decades of communist rule to our homeland. Down came the Iron Curtain and we were given an ultimatum. The Czechoslovak embassy in Tehran ordered my father to take his family and return home. When he refused (he was a staunch anti-communist), we were stripped of our citizenship and our passports annulled. Thus began our 6-year saga as stateless refugees in Iran.

Eventually, we were granted Iranian citizenship, fresh passports, and our foreign travels could resume. Ultimately, because of my own migrations in later years, I became a citizen of four countries. I cherish the three valid passports I now hold because they give me great travel flexibility.

Given your international background, how many languages do you speak? And which country do you feel you ‘belong’ to most?

Thanks to my father’s insistence, we spoke Czech at home even though we were not living in Czechoslovakia. Living in a Kenya run by the British made it natural that I would be schooled in English. While we were still in Kenya, I picked up enough Swahili to make myself understood, but I no longer speak this Bantu language. When we got to Iran, it wasn’t long before I became fluent in Persian (Farsi) which is an Indo-European language, but is written in Arabic characters. At school, I took French classes, so learnt French as well. Dad was fluent in German and nudged me to attend the Goethe Institut in Tehran to learn German, so I did. Finally, because Czech is a Slavic language, I had little trouble learning another Slavic tongue—Russian.

Today, I am fluent in six languages and read/write them as well. Persian and Arabic scripts are similar, so I can read a little Arabic. And if you bring out the egg beater and stir up the linguistic sauce in a bowl for Romance languages, the mix allows me to understand what I read in Italian. Because my wife is Japanese (her given and maiden names translate as Beautiful Snow At the Bottom of the Rice Paddy), I’m sometimes able to decipher Japanese writing if it’s written in hiragana or katakana (with kanji characters, I’m lost). Why does a language need three writing systems? I feel sorry for Japanese school children learning to read and write; they need to master all three.

My goal is to master two more tongues—Spanish and Arabic. Then, I’ll give it a rest. And hide somewhere in Paraguay. . .or in Morocco’s Tangier, birthplace of Ibn Battutah, the greatest medieval traveller of all, and settle into reading Alf Layla wa Layla (A Thousand and One Nights) in its original Arabic.

So, which country do I feel I ‘belong’ to most? Figuring out to whom I belong is like finding myself encircled by several mothers jostling each other to claim the same child. My ancestry stems from France, Spain, Morocco and Austria and, many generations later, from the Czech Republic. I feel close to the Czech people (language is a mighty bond) but Persia tugs at my heartstrings too. After all, I grew up there, was schooled there, and know the people and their ways. But what about the 22 years I spent in Canada, and another 21 in Australia, the 3 years in England, and the 7 years in Kenya, and the 2 years in Japan. . .do you see the problem? I have only one heart.

The question I dread emerges whenever fellow travellers ask, “Where are you from?” I wish I had the courage to reply, “Once upon a time, in a faraway land, there was a solitary sperm. And it was seeking to meet a pretty egg and befriend it, then be invited in to fertilise it, and see the cells happily multiply into millions, then billions, guided by the laws of genetics. Where am I from? I’m from my mother’s womb.”

You have travelled considerably and still do. Which countries have most surprised you, positively or negatively?

Travel brings many surprises. Where could I start? What we hear on the radio, or watch on TV, or read in the papers colours our perceptions of the world’s countries, cultures and peoples. Even good travel books and documentary films will give the reader or viewer a specific viewpoint, that is not one’s own, but rather that of the writer or film maker. Thus, when a traveller begins to see for herself or himself, there are bound to be surprises. You will know it when you see it. Examples follow, below.

How shocked I was at the mess of an Eternal City they call Rome: traffic congestion, air pollution, black grime on ancient monuments, rude or impatient drivers, curt and unhelpful service personnel, and Eternal Noise. Augustus Caesar would be shocked too. He had transformed Rome into a lavishly beautified capital of the Roman Empire. His last public words before dying were, “Behold, I found Rome of clay, and leave her to you of marble.” I didn’t wait until death was approaching to say, “Behold, I found Rome today, and leave her to you—in a hurry.”

Many European cities are suffering the same fate: Vienna to my eyes was a cultural and civic jewel in the 1960s. Today, I shudder at the deterioration—traffic bottlenecks, slum areas, greying statues in public places, trash in the city parks, graffiti-decorated hangouts, urban decay, overcrowded plazas and transport hubs . . .Is this what mass tourism has done to European cities, or is this the inevitable outcome of urban population growth?

One needs to make two visits, at least 20 years apart, in order to clearly perceive the changes that have taken place in many large cities around the world—in my case, Vienna, Prague, Vancouver, Los Angeles, San Diego, Miami, Cairo, Nairobi, Brisbane. Population growth means greater pressures on urban land and facilities. On top of this, ever-increasing mass tourism in “brand-name-destination” cities accelerates the physical deterioration and eats away at the former attractiveness of historically great metropolises.

Recently, some destinations have introduced visitor limits and are capping the number of tourist permits issued annually. Among these, are Chile’s Torres del Paine National Park, Machu Picchu, Fernando de Noronha, Galápagos Islands, and Antarctica. Now, Venice and Iceland, too, are seeking ways to limit visitor numbers.

But let me flip the Roman coin. If Caesar’s image is on the obverse, let the reverse show Venus, the goddess of beauty and love, and present the surprises that delighted my soul:

Iceland’s astonishing landscapes; the exotic and unafraid wildlife in the Galapagos archipelago; the soft- spoken and helpful townspeople of Southern Africa, Cuba, and Grise Fiord on Ellesmere Island; the magnificent desolation in the wilderness of Botswana and Namibia; the charming simplicity of communities in Malawi, Greenland, central Myanmar, Vanuatu and Himachal Pradesh; the unique and difficult terrain of Madagascar and Canada’s Far North; the head-spinning peaks and mountain passes of southern Peru and northern Bolivia; the catatumbo lightning of Lake Maracaibo, Venezuela; the spectacularly quiet fiords and inlets of Baffin Island; the deafeningly raucous squawks of the uncountable nesting penguins on South Georgia and Macquarie Island. And, of course, the majestic Islamic architecture of Esfahan and Samarkand, Istanbul and Taj Mahal.

My list of pleasant surprises is as extensive as the guide books put out by Lonely Planet. Indochina seduces one with the general humility of its denizens; Denmark, Costa Rica, and Japan are models of civility and citizen politeness toward strangers. Uzbekistan is so steeped in history that it’s difficult to comprehend the myriad influences: plant yourself in Samarkand and you’re standing on the soil of great empires—the Persian Empire, Alexander’s Empire, Sasanian Empire, Safavid Empire, the Mongol Empire. You are the latest to see what the followers of Hinduism, Buddhism, Christianity, and Islam have left behind.

Finally, I look at visiting poor countries with a mind-set tempered by lowered expectations. To me, these nations are the genuine expressions of humanity—simple people, finding joy in small things, refreshingly down to earth, signalling their hospitality and open friendliness, taking their time to appreciate each day, showing respect for the wisdom of old age. Not having the materialistic obsessions and narrow self-interest that are so common in developed nations, their laughter comes easily and their child-like curiosity is a delight to experience.

I empathize with their economic situation—mostly brought down on their heads by corrupt leaders, limited-vision dictators, and dishonest government officials. But, poor as they are, I am so often surprised by their level of education. They seem to value learning and knowing about the world. In general, I find that people in poor countries have an openness to foreign visitors and are very approachable when you show an interest in their lives. This is true even in tiny villages and rural areas where there is a language barrier.

They seem free of the economic arrogance and narcissism of so many citizens in developed economies—the so-called First-World—who know little of the world outside their own borders, who so often fail to look up and look around because their noses are continually buried in their smart phones, who have sleepless nights during their travels because the stock markets have fallen and their shares are down, who complain because the hotel they are staying in has air-conditioning problems, who have no patience for the slow local service, who expect their local travel guide to be an encyclopaedia of knowledge—you get the picture…

You are a travel writer nowadays. If we may ask, where do you write? What kind of travel-style do you feel most comfortable writing about?

Given the life stage I now occupy, after a 27-year university career as an academic, I feel comfortable writing for older audiences. These people are genuine OPALS—older people with active life styles—typically in the 50-plus age category, who want to travel and expand their experiential boundaries. As well, I would like to stimulate non-travellers (armchair travellers) to remain curious about the world outside their own surroundings and who welcome the notion of “discovering” things about people and places in other corners of the Planet. These are the people who would follow David Attenborough or Michael Palin down a fibre optic cable, to places they would never otherwise experience.

Retirees, with plenty of time for travel, have a different set of criteria for what represents an enjoyable and exciting travel experience. Their criteria are quite different from what younger people would consider exciting and worthwhile. To OPALS, tearing up and down mountain trails or paddling furiously through treacherous river rapids is not essential for a rewarding travel experience. Soft adventure is better suited to these travellers. And they want immersion into alien cultures without going native. In my travel articles, I emphasise the fascinating dimensions of cultural diversity, the uniqueness of a destination’s physical qualities, or the historic significance of a place visited.

Over the years, I’ve had a good working relationship contributing articles to 50 something magazine, an Australian publication with a readership of 356,000.

When you travel, do you have any specific aims apart from global coverage?

One of my main travel aims is to connect with the younger generation wherever I visit. These children are the young citizens of Planet Earth. They will touch the future, long after I am gone. Whenever possible, I try to visit them, talk to them, excite them about what Earth has to offer. This is not always possible but, whenever I am given the chance, I visit their schools, their playgrounds, their classrooms and give them a short talk about the world beyond their surroundings. My aim is to make them aware of the world they will inhabit as adults.

Sometimes, it is possible to give them an idea of the place I come from, or some distant land that has exotic creatures and flora, or native people that dress or eat differently. Examples are, Canada’s rivers, mountains, climate and native animals; Australia’s geography, lifestyles and wildlife, Antarctica’s bizarre landscapes and animals, or Africa’s snakes and undersea life. Occasionally, I get very lucky and can give the children a PowerPoint presentation on my laptop loaded with photos. This is when I get a lot of questions at the end, before they need to hurry off to their next class.

Before leaving home, I try to pack (not always possible) school exercise books, notepads, colouring books, pencils, and small souvenirs that typify where I live—things the children in poorer nations cannot get enough of, or have no access to. If a village school principal tells me that they need more bicycles for students who live too far away to walk to school, I will pitch in and help the school buy one or two pedal bikes. In many places, there is no electric lighting after dark; so the trick is to donate locally available small lanterns with solar panels that get charged by the sun’s rays and allow a schoolchild to study at night.

Finally, at the end of my travels, I usually give away personal items to the locals—my guides and drivers, ship’s crew or cabin staff, service workers in lodges or at tour booking counters, village heads—things no longer needed that I don’t have to take home (hiking boots, shoes or sandals, knee-high gumboots, jacket, day pack, pullover, thick socks, hats, maps, flashlight/torch, paperback novel, the guide books I had brought). This lightens my baggage on the typically-long homeward journey. And it offers something of myself to the local people I’ve met in far-off lands, in return for having been enriched by them.

You also have a website called Know Your Earth. What are your aims with this website?

My www.KnowYourEarth.net website offers a different way for people to really get to know the only planet they will ever experience. Earth is home to, not only a vast diversity of cultures and inhabited places (human geography), but also a huge variation in physical geography.

To truly experience Earth, one needs to go beyond politically defined places. Experiencing a planet that has been divided into politically separate entities and destinations (countries, states, provinces, territories, geographical jurisdictions, possessions, dependencies, enclaves, etc.) is a major challenge, of course. This is one reason why I joined The Best Travelled to keep track of my travels.

But man-made borders are not Earth’s borders. The Know Your Earth Travel Challenge for planetary coverage allows the traveller to experience, feel and absorb every aspect of Earth’s physical and habitational dimensions. Planet Earth uses different boundaries to reveal herself to you. These boundaries are based on latitudes and longitudes.

Adventure travellers who adopt as their goal the Know Your Earth systematic guide for navigating the Home Planet will come to appreciate and comprehend the full extent of Earth’s physical, natural and cultural diversity. You will not be able to do this on any other planet.

So, here’s a way to let Earth show you what she’s really got. Start with a globe or world map and divide the Earth into 10-degree-wide slices of longitude, going right around the globe. By doing this, you get 36 slices of longitude (360 degrees, partitioned into 10-degree slices).

Next divide the Earth from South Pole to North Pole into 10-degree-wide bands: 90S to 80S; 80S to 70S; 70S to 60S. . .and so forth. Keep

creating bands in this way, past the equator, all the way to 80N to 90N.

You have now defined18 such 10-degree-wide bands of latitude.

Now go visit some place—any place—within each of the 36 longitude slices and each of the 18 latitude bands, and see what Planet Earth can throw at you, or thrill you with, or teach you. Wow! What a way to discover your home planet!

And when you’ve done that, do remember to tell your grandchildren about your experiences.

You are now based in Australia. What are some hidden gems of the country that many people don’t know about but you would recommend?

I don’t know Australia as well as I should. It’s a case of the old truism: when something lies at your doorstep, you fall into the trap of thinking, “It’s close by; it’ll still be there when eventually I get around to seeing it.”

But there’s also the sheer size of the country. If you like to get close to nature and culture, Australia has 19 UNESCO World Heritage sites and more than 500 national parks that occupy 4 percent of the land area of the world’s sixth largest country. Compare this to the 59 national parks in the United States.

In the early-20th century, Canadian Prime Minister Mackenzie King remarked that, if some countries have too much history, Canada has too much geography.

The same could be said of Australia: too much geography; not enough people. The land mass is so enormous it is sometimes classed as Earth’s smallest and least inhabited continent. Sandwiched between the Pacific and Indian Oceans, the vast interior is arid, mostly flat, and very sparsely inhabited. One needs to fly across Australia because there is no well-developed road network in the interior. Most overseas visitors are unaware that the distance between Brisbane on the Pacific coast and Perth on the Indian Ocean is the same distance you cover when flying from New York to Los Angeles.

If you think you will see Australia by visiting for two weeks, you are sadly mistaken. Should your budget allow, I would recommend at least two months. If you don’t have two months, consider making multiple visits to different parts of the continent. Take Russia, Canada, USA, China, Brazil—what could a visitor to any one of Planet Earth’s five largest countries see in two weeks? And Australia comes in sixth on this list.

A few “hidden gems” of Australia that I would recommend are Tasmania, Kangaroo Island, Kakadu, and Macquarie Island.

The island of Tasmania was once connected to the Australian mainland when sea levels were much lower (about 15,000 years ago). Some Tasmanian plant species are related to those of South America and New Zealand when these three lands were still part of the supercontinent of Gondwana, 50 million years ago. More recently, Tasmania was once a penal colony of the British Empire and called Van Diemen’s Land. Today, it is Australia’s smallest state with Hobart as its capital.

When you think of Tasmania, think natural. Half of Tasmania’s total area lies in reserves, national parks, and a World Heritage wilderness. It is Australia’s most mountainous and most ecologically conservative state. The island is densely forested and includes some of the last temperate rain forests in the Southern Hemisphere.

Tasmania is one of the world’s best places for multi-day guided wilderness walking tours—rain forest walks, coastal walks, island treks, national park treks. If Africa has the Big Five in majestic animals, “Tassie” has the Big Seven in magnificent walks. It is also superb for cycling tours, kayaking and rafting. Visitors can take night tours of haunted buildings in Port Arthur, one of Australia’s most haunted places. As for gastronomic delights, the variety and quality of Tasmanian boutique cheeses are legendary.

A major event is the annual Sydney to Hobart yacht race, one of the world’s top three and most gruelling offshore yacht races. Established in 1945, it starts on December 26 (Boxing Day) and covers 1,163km. Finally, the iconic but endangered Tasmanian devil, a nasty-tempered carnivorous marsupial, is found in the wild only in Tasmania.

Tough yacht races, tougher animal jaws, and the toughest gun-control laws in Australia. That’s Tasmania for you.

Kangaroo Island, in South Australia, is Australia’s third largest island. I call it a microcosm of Australia; if you want to see what Australia’s nature and wildlife look like, come to Kangaroo Island. In Flinders Chase National Park you will find Remarkable Rocks, a truly remarkable collection of 500-million-year-old granite boulders, weathered by constant wind and looking like Henry Moore sculptures. In different parts of the island you will find Australian sea lions, kangaroo, echidna, goanna, bandicoot, wallaby, possum, New Zealand fur seal, koala, and platypus. Only in Australia do you find an animal that defecates cube-shaped excrement—the wombat. And you will find them on Kangaroo Island as well.

Drive 3,200 km north from Kangaroo Island and you will get to Darwin, in Australia’s Northern Territory. If you like the idea of taking the world’s longest bus ride—97 hours and 20 minutes—across an entire continent, use a combination of ferry and coach to get from Kangaroo Island to South Australia’s capital, Adelaide, and board the Greyhound bus there. If you have 14 days, you can board The Ghan passenger train in Adelaide and see Australia’s interior all the way to Darwin.

Once you’re in Darwin, head south into another Aussie jewel—Kakadu National Park. Close your eyes and imagine a 20,000-square kilometre national park the size of Wales or Massachusetts, and four times the size of Grand Canyon National Park. There are multi-day guided tours to this World Heritage site. Here you will find cave paintings, rock carvings and archaeological sites showing the way of life of the region’s inhabitants, from the hunter-gatherers of prehistoric times to the Aboriginal people still living here after more than 50,000 years. Kakadu is managed by Aborigines and the park protects an extraordinary number of plant and animal species; its ecosystems and landscapes are spectacular.

When you visit Australia, pack plenty of noughts and zeroes inside your head. Everything in this country is in thousands or millions, not hundreds. Examples: America is 240 years old; these Aborigines have lived here through a time period that’s more than 200 times the age of the United States. By the time the Great Pyramid of Giza was completed, Aboriginal people had been inhabiting this land for 46,000 years.

Let’s move on to Macquarie Island. Another jewel in the Australian crown. This World Heritage site is very far away and tiny—the island is 34km long and 5km wide. From Tasmania, you need to sail halfway to Antarctica and to the edge of the Southern Ocean, to get there. The Southern Ocean? Yes, Earth has five oceans, not four. The Southern Ocean encircles the Antarctic continent, with the generally accepted northern limit of this ocean at 60°S latitude.

The only way to get to Macquarie is by ice strengthened ship. Why would you want to sail 1,550 kilometres south from Hobart, through very rough seas for 3 or 4 days, to come here?

Because it’s party time on the beaches of this island. Here, you will get up close and personal to rock hopper penguins, and dance around Macquarie shags and Royal penguins which are endemic breeders. The majestic king penguins and Gentoo penguins also breed here in large numbers. Then you can spend time photographing the sub Antarctic fur seals, Antarctic fur seals, New Zealand fur seals and southern elephant seals — over 80,000 individuals. Never before have you attended a noisier love party, and these creatures are not even on drugs. On the beaches, there’s more sex and violence among the elephant seals than you will find on late-night television. The island supports about 3.5 million breeding seabirds of 13 species. Go party in Macquarie; you won’t regret it.

So what are your future travel aims? Any concrete travel plans for the rest of 2017?

Future travel plans focus on places I have not yet explored, and a few repeat destinations that I want to explore in more depth. Among the seven continental sisters, Antarctica is my favourite. In the next few years, I plan to pay Sister Antarctica a third visit, with the aim this time of experiencing the Australian Antarctic Territory, Mawson’s Hut, Balleny Islands and the French scientific station of Dumont d’Urville, near where the documentary film March of the Penguins was shot. It’s a very pricey 30-day expedition; and I envision making a great voyage of discovery to my local bank manager.

Closer to home, are plans to travel to places I should have covered long ago but have not visited—Greater Sunda Islands, Lesser Sunda Islands, Timor, Sulawesi, Moluccas, West Papua, Papua New Guinea, Solomon Islands, and New Caledonia.

One major travel aim is to sail across the Indian Ocean. Having sailed across the Arctic Ocean (by Russian icebreaker to the North Geographic Pole), the Southern Ocean (by ice-strengthened ship to McMurdo Station in Antarctica), the Pacific and the Atlantic, it seems fitting to complete the goal of crossing all five oceans by boarding a cargo ship in, say, Durban and sailing eastwards to Fremantle, Australia.

Finally, a question we always ask. If you could invite any 4 people from any period of human history to a dinner, who would your guests be and why?

I would change the rules a little bit by inviting 4 people separately, and spending much more time with each, than just over a dinner. I envision a week-long, one-on-one chat with each guest in order to capture his or her insights on what makes a well-travelled person. The people chosen would be currently active in their field of research, highly accomplished and experienced, and willing to consider the problem from various angles. The four—two women and two men—would be a cultural anthropologist, a cognitive scientist, a personality psychologist, and a physical geographer.

I would get them to consider questions like these, then listen carefully and record their thoughts:

What does it mean to be well travelled? How do we define this? Are there certain standards that need to be met before a person can be considered well travelled?

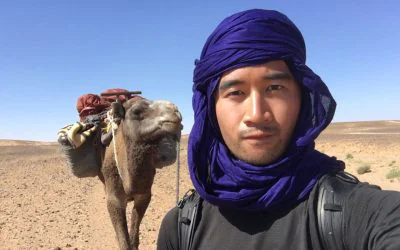

The photos in this interview are from Thomas’s personal collection, showing his work with children in Malawi, Greenland, China, Australia, Madagascar and Indonesia.