The Caribbean is full of sun, sea, and surprises. In this blog, written by Sue, you’ll discover hidden islands brimming with adventure, from quiet reefs and lush hills to historic towns and local culture. Whether you love nature, history, or just new experiences, these islands have something unforgettable for everyone. Take it away Sue..

The Caribbean is always a great place to travel, with its sublime scenery, warm weather and holiday vibe. And it’s also steeped in complicated colonial history. But I’m surprised to discover that quite a large part of the Kingdom of the Netherlands is actually located in the Caribbean. These are some less well known islands of the area: Bonaire, Saba and Sint Eustatius. As of writing, 371 Nomads have been to Saba, 259 to Statia and 966 to Bonaire. So they’re begging to be explored.

Facts and Factoids

- Bonaire, Saba and Sint Eustatius (usually called Statia, as it’s a bit of a mouthful) are the Caribbean Netherlands, although the term ‘Caribbean Netherlands’ is often used loosely to refer to all of the islands in the Dutch Caribbean. They’re also known as the BES Islands, for obvious reasons. These are municipalities, as distinct from Aruba, Curacao, and Sint Maarten, which are constituent countries of the Dutch kingdom.

- English, Dutch and Spanish are spoken alongside the local tongue, Papiamento, in Bonaire.

- Dutch and English are spoken in Saba and Sint Eustatius

- The currency in all three islands is the US dollar.

- In 2012, the islands of the Caribbean Netherlands voted for the first time, in the 2012 Dutch general election. due to now being special municipalities of the Kingdom of the Netherlands.

Which BES Island is the Best?

Bonaire – A Diver’s Paradise

Bonaire is very small and dry, and is much further south than the other two islands, but has real character and a reputation for the best diving in the Caribbean. It’s known as “Diver’s Paradise”,(or failing that “The Velcro Island”, and “Dushi Bonaire”). Including the islet of Klein Bonaire it is one of the Leeward Antilles, located close to the coast of Venezuela, along with the other ABC Islands, Aruba and Curacao. So, Bonaire is geographically part of South America and better known as part of another island group.

The ABC Islands earliest known inhabitants were the Caquetio, a branch of the Arawak. They came by canoe from Venezuela in about 1000 AD. In 1499, Spanish explorer, Alonso de Ojeda arrived at Curaçao and a neighbouring island that was almost certainly Bonaire. He is said to have called the islands Las Islas de los Gigantes, or Islands of the Giants, due to the size of the native inhabitants. By 1527, the Spanish had formed a government and established Catholicism on the islands. However, the Spanish conquerors dubbed the three ABC Islands ‘The Useless Islands’, as they could find no mineral wealth.

Nevertheless, the Spanish remained, allowing the area to become a hotbed of piracy and ruining the indigenous culture. until they conceded the islands to the Dutch, in the Eighty Years War, Ironically, gold was later found on Aruba. During the Napoleonic Wars, the Netherlands lost control of Aruba, Bonaire and Curaçao to the British twice, during the early 1800s. The ABC islands were returned to the Netherlands, under the Anglo-Dutch Treaty of 1814.

Getting into Bonaire

Most flights into the ABC Islands arrive in Aruba. The onward journey from Aruba is only half an hour, crossing Curaçao on the way. The ABCs are not arranged in alphabetical order, in the ocean. A late arrival in Bonaire, but a happy one. ‘Have a good stay,’ beams the efficient lady on immigration. The reception at my new hotel, a dive resort is less effusive. They’re making me pay to rent the safe in my room. I’ve never come across that one before, when the safe is already in the room. ‘Otherwise we will lock it up…’

Watching Wildlife on Bonaire

I’m having a quiet day in the sun, while I suss out the locality. I’ve been to the local Chinese supermarket (expensive). Like Aruba, the island is flat and arid, but without the wide sand beaches. The area around the hotel is hardly scenic. There is a water processing plant, cactus fencing and a view across to an even flatter, smaller island, Klein Bonaire, half a mile away.I’ve tested the snorkelling off the hotel jetty. There’s a drop-off to a reef five metres out, but the wind and boats have kicked up sand and visibility isn’t great. There are pair of tarpons – enormous – under the pier though. They lurk around, as the hotel kitchen tips the scraps of fish into the sea for them.

I wind up the afternoon with a massage. In between, I’ve been watching the lizards and iguanas scurry round the pool and teeny humming birds sneaking nectar from scarlet tube-shaped blossoms. Those birds move fast. They might need to, as there’s also a black and ginger cat, who has taken possession of my patio.

Klein Bonaire

Snorkelling at Klein Bonaire. I spend an hour and a half happily drifting along reefs here. Like all coral in the Caribbean this is not particularly colourful, but at least it’s alive and there’s plenty of interesting animal life: eagle rays, angelfish, barracuda, turtles, eels, varieties of parrotfish and the usual assortment of striped bannerfish and shoals of minuscule blue flashes. The stoplight parrotfish is common here. It’s one of those fish that changes sex, in this case from female to male. It must be an interesting life.

My very organised Dutch boat hosts say that Klein Bonaire used to be owned by Harry Belafonte. It’s where he wrote Island in the Sun.

Round and About Bonaire

It’s a truism that the most rewarding travel happens when you get a local to show you round. Today, Oyo (short for Gregorio) is taking me on a figure of eight tour round Bonaire, in his Kia. He is quietly knowledgeable and goes out of his way to stop for photos. It’s a surprisingly interesting and diverse place.

The reef runs right round the island, which is almost entirely coral and limestone, as a result. The entire coastline of Bonaire was designated a marine sanctuary in 1979. with over 350 species of fish and 60 species of coral. There are more than 400 caves hiding here too.

The drop-off is really close to the shore, all up the western coast, so divers can access without boats. All of the sites are marked with yellow stones. ‘Thousand Steps’ (there’re really only 67 Oyo says), though access looks rather too adventurous, across slippy rocks in some. There’s a stripe of turquoise running along the coast, immediately turning cyan at the reef, so it’s very easy to see where it is.

The land rises to 2000 metres in the north, where there are some small mountains, lakes and a few flamingos. The limestone hills and cliffs are entirely finger cactus covered. It’s the only thing that grows (they make liqueur and slimy ‘healthy’ soup from it). All the food has to be imported. There are tall metal windmills running pumps (this is the Netherlands after all), numerous small ranches and some goats scattered across the countryside. Road signs also warn of wild donkeys and sure enough we encounter a small, shy group, grazing in the scrub.

Kralendijk

Rincon, famous for its annual festival, visited by the king and queen, is the only town outside the capital, Kralendijk (Dutch for coral reef). The latter sits at the centre of our figure of eight, so is encountered twice. It’s unsurprisingly, a smaller version of Philipsburg, in Sint Maarten, with brightly painted shops cafes and bars and Dutch gables, geared up to cater to the cruise ship market.

South Bonaire

There’s a different sight around every corner. In the south, are commercial salt pans, more lakes, some very pink, flamingos and a lighthouse. Apparently, Bonaire has one of the largest flocks of flamingos in the world. To the west, more diving sites, sea bird covered rocks, restored slave huts and a bay where the sky is dotted with the bright sails of kite surfers. To the east, sea grass lagoons in a sheltered sandy bay, this one swarming with windsurfers. Colourful and fascinating. (Bonaire has produced several world champion wind surfers and kite surfers.) Read more about the ABC Islands here.

Saba, Unspoiled Queen of the Caribbean

Saba and Sint Eustatius are (there is some debate about this) part of the Windward Islands and are volcanic and hilly, with little ground suitable for agriculture. These Dutch islands have historically, totally passed me by. I’m really unsure what to expect. But Saba dubs itself ‘The Unspoiled Queen of the Caribbean’, so that’s promising.

Saba is the smallest special municipality (officially “public body”) of the Netherlands. (Say it Sabre -say-bur- if you’re speaking English and Sah-bah if you’re speaking Dutch). Indeed, it is the smallest territory by permanent population in the Americas. The number of inhabitants was 1,911 in January 2022. That’s a population density of just 380 per square mile.

Ferry, the Safe Way to get to Saba?

You can fly into both Saba and Sint Eustatius from Sint Maarten. But, I’m travelling to Saba the cheap way, on the ferry, from St Kitts. It’s a two and a half hour journey and the forecast says it’s gusting 30 mph, so I’ve downed two travel sick pills and found a seat outside. It wasn’t easy. There was a scrimmage to get on board, even though the woman in charge just called for families with children. To be fair, she didn’t say anything about the age of the children. Makana Ferries promise a modern experience and a bar. A man brings round bottles of water in a plastic bag and says that’s it. At least they’re free. There are no safety announcements.

The crews’ tee shirts suggest a triangular arrangement of islands, but in fact mine is an almost linear journey north-west. St Kitts, Sint Eustatius (I’m coming back to this island), Saba. Great panoramic views of cloud nestling on the mountains of St Kitts and Brimstone Hill Fort, from the boat. Then, once past the leeward side of the island, we’re lurching alarmingly in the Atlantic swell, from the starboard side. It’s a little too exhilarating and the passengers practise their ‘I’m not scared’ faces. I’ve made sure I’m sitting on the left. Even so, at times, the spray rolls right across the top of the catamaran, cascading onto the deck. It drizzles a little too, but it’s hard to tell when.

Suitably damp, I arrive at Port Bay Harbor, somehow squidged in, against the cliffs, below The Bottom. This is the name of the capital of Saba, even though it’s up top, in a high valley. The captain is warning the passengers that it’s going to get really wet from now on, as they dog leg north east up to Sint Maarten. I’m glad I’m departing.

Saba is Stunning

Saba juts incredibly from the sea, soars even, with slopes that are steep and sheer in places. It mainly consists of the aptly and unusually named Mount Scenery. (At 887 metres this is the highest point in all the Kingdom of the Netherlands).

No wonder Christopher Columbus didn’t land here, in 1493, deterred by the perilous crags. That didn’t stop him naming the island St Cristobal, after himself, but his name didn’t last very long and it quickly became Saba. Though no-one is sure why. The impenetrable rocks also explain why Saba became a key refuge for smugglers and pirates.

The road here is a masterpiece of engineering, a concrete strip, lined with a wall, which zig zags across the peaks, like the Great Wall of China. Several engineers claimed that a road in Saba was impossible, but Saban, Josephus Lambert Hassell began building in 1938 (without machines). It took 20 years to complete The Road that Could Not be Built, linking port to airport, with spurs off, into the little hamlets. Today, it’s usually just called The Road.

I take to The Road. It’s a memorable and stunning drive. From diminutive The Bottom, (there’s a medical school here too, which accounts for 25% of the population of the island). I wind steadily (with taxi driver Cyril), to the smallest village, St Johns (nevertheless home to both primary and secondary schools) and then across the island to Windwardside, the main tourist area. The last village, which I haven’t seen yet, is Hell’s Gate (there’s an old sulphur mine below), though the vicar likes people to call it Zion’s Hill. So, that’s what the signboard says, though the locals aren’t always very obedient.

Windwardside, the Tourist Centre of Saba

The hillsides are dotted with houses, nearly all white wood, with corrugated red roofs, gingerbread frilly eaves and shuttered windows, which have dark green frames. Though some rebellious types have gone for all white. The churches have shutters also and pointy witch hat spires. It’s all impossibly cute. Windwardside is a toy village, with plate glass, supermarkets cafes and restaurants. There’s a tourist information centre and signboards loaded with historical and geographical information. A bank with a covered ATM. It’s all USD here, English signage and American accents. Though the folk I’ve met tell me they were born here. Apparently, 30% are Dutch speaking.

And, my goodness, the roads are steep and winding. I’m staying in some eco-cottages, which are 70 ache inducing steps above the road. I think they should install an oxygen station half way up. The views are great, of course, out across the Caribbean, though obscured by the rain forest. And we really are in the cloud forest here. A feast of vegetation, palms waving, bushes laden with exotic blooms, creepers, royal palms, elephant ears, mangos, bananas and much more. The tag line Unspoiled Queen of the Caribbean seems appropriate.

On Mount Booby

White (and black ) cloud puffs (carrying more drizzle) waft above my head, as I slumber by the little pool. The cottages are built on the side of Mount Booby, an apt name for me at the moment. There are trails up to the top, but The Seventy Steps is enough for me.

The damp accounts for the moss on the steps, but there’s a fine line between eco and not caring for something. I think it’s being crossed here. There are broken steps, leaves un-swept and a pile of rubbish in a plastic bag. All the furniture is ‘rustic’ as the paint has peeled off and the fencing round my cottage is algae covered and could definitely do with a lick of paint. But maybe that’s not eco friendly?

My cottage is as basic as it gets. Two single beds (the blurb says I can push them to make a double, but that looks like a Herculean task that would leave no room to get into them) and a table. The toilet and shower are outside. In separate cubicles. The shower is just a dribble. There’s no lock on the door, just a hook, that I haven’t got the strength (or knack) to engage. There’s one other guy staying here, but he’s clearly not up for conversation. He just manages to squeeze out, ‘Hi’, as he scuttles past.

It’s not entirely peaceful, however. I’ve also been adopted by the local cat, who commandeers the best spot on my sunbed. And there are numerous dogs around. Barking competitions fill the air, as dusk draws in. When the canine chorus pause for breath, the insect gamelan cuts in. A continuous chirrup from the trees, mainly harmonious, but intermittently a loud creaking and occasionally a more raucous buzzing, like an electrical device that’s gone wrong.

Wandering (or not) in Windwardside

Marooned by the steps, I’m spending my days lounging by the pool., the water in which is dotted with leaves. It may or may not get strained in the morning. The pump is on semi strike. Hot sun, cloud, drizzle, heavy but short showers, in rotation, are the order of the day. Tiny anole lizards skitter by, peeping round corners (they always skitter), hummingbirds hover in the undergrowth and butterflies skip around the bougainvillea.

Windwardside is 1850 feet away, as the crow flies, from the bottom of The Seventy Steps. Up a slope, then down again, a very steep hill, as are all the roads here, it transpires. It’s the reverse on the way back of course, which, combined with aforesaid Seventy Steps, is exhausting. Fortunately, there’s sometimes a kind soul who offers a lift, for some of the road section at least. It’s a small island, so I assume I’m safe and besides, I can’t afford to worry about stranger danger, when my lungs are about to collapse.

The village rewards exploration, with its museum, numerous information boards (history and natural history) and chocolate box houses. Two well stocked, if expensive, supermarkets. A scuba centre, catering for the diving, for which the island is famous. Saba is surrounded by a Marine Park. Snorkelling is not so good, I’ve read, and besides it’s very windy. The locals say the Christmas winds have come early.

One of the information boards tells me about the scarlet flowered flamboyant tree. But that flowers in the summer and, I discover, is not to be confused with the gorgeously in flower, at the moment, African tulip tree. Another of the signboards focuses on lacemaking (and there’s still a lace shop). The women here learned to make lace (introduced by a nun from Venezuela). For a while, this was the primary source of revenue and Saba for some time, became known as ‘The Island of Women’.

The food is good, in the restaurants I’ve sampled. Divine coconut shrimp curry in the Tropic Café at Juliana’s Hotel. Behind Windwardside towers Mount Scenery, blanketed in greenery. A hiker’s paradise. So I’m told.

Round and About in Saba

After humping my bag up The Seventy Steps Cyril promised me an island tour, before my return to the ferry. ‘It’s easier to do it all in one trip’, he suggests. But, ringing him up in the morning to confirm, it transpires he’s now agreed to take someone else to the airport, so I’m getting two halves of a tour, one earlier in the day.

Cyril drives me a little way up Mount Scenery and then along the one main road, up to Zion’s Hill (Hells’ Gate), with stunning views beneath. Velvety folded slopes, running to a foam splashed cove, Spring Bay. Further on, the airport, beyond an even more picturesque crag ringed headland – Tide Pools. Juancho E Yrausquin Airport is tiny, with a short runway (ostensibly the shortest in the world), almost surrounded by ocean and blocked at the end, by the sheer mountainside.

You can buy ‘I survived landing at Saba’ tee shirts’. Despite this, there’s never been an accident at the airport. A peek up a couple more spur roads, creeping round one of the local’s gardens to admire yet another scenic drop to the sea. (‘He won’t mind’, says Cyril.) Cyril’s worried about his new car. He says it’s making strange noises and odd warning lights are appearing on the dashboard. I point out that it’s a hybrid and it’s going to go quiet at times. It turns out that the warning lights come on, when he inadvertently presses switches on the centre of his wheel. He thanks me for fixing his vehicle.

Cyril doesn’t turn up to collect me for the second half of my tour, until it’s almost dark. He’s still got his airport pick up in the car. We have words. He claims to be very sorry, as we scoot inside the Church of the Sacred Heart, at The Bottom. He’s even praying for forgiveness. I’m not sure God can help here. They’re big on Christmas lights on Saba, so there are illuminated houses to admire, at least. The beach at Wells Bay (famous Diamond Rock at the end of the point), on my list of Highlights To Tick Off, is just visible in the inky dusk.

Farewell to Saba – and Cyril

Then, we arrive at the ferry port. ‘You’re late’, says the check in clerk, even though Cyril has told me I have plenty of time. I’m now instructed that I should be there an hour before departure. It would be helpful if they gave you that information when they issue the tickets. But we do leave early, as the boat is ahead of schedule and all are on board. None of this stops Cyril from demanding 40 USD and declaring he will make up for it all by sending me a ticket to come back. He also wants to call me on Christmas Day, to play a song on his guitar for me. Thankfully, he doesn’t have my phone number.

Sint Eustatius (Statia), The Golden Rock

I stopped by Sint Eustatius on the outward journey to Saba and it didn’t look exactly, how shall I put it, imposing. This island has more historical tales to tell than Saba though. Perhaps they’ll pique the interest.

Big Dipper to Statia

The ferry ride to Statia, is, if anything. even rougher than the journey out. The pitch dark of night doesn’t help, as we hang onto the railings, while the boat tosses up down and swings from side to side. I’m not keen on fairground rides anyway and this is like being on a continuous Big Dipper. I’ve never known time pass so slowly. Everyone sitting outside with me is vowing that they’re going to fly back.

Statia, Background

Columbus possibly also saw Statia, but the first firm sighting was made by Francis Drake and John Hawkins. The island’s name, Sint Eustatius, is Dutch for Saint Eustace, but it was previously known as Nieuw Zeeland (‘New Zeeland’), after the Zeelanders who settled there in the 1630s. (I’ve heard that name somewhere before.) The indigenous, Arawak name for the island is Aloi meaning ‘cashew island’.

When they were under Dutch control (as of 1678), the islands of St. Eustatius, Sint Maarten and Saba fell under the direct command of the Dutch West India Company, with a commander stationed on St. Eustatius, to govern all three. The Dutch eventually gained full control in 1816, still generally ruling from Sint Eustatius, where the main plantation owners (sugar, tobacco, indigo and rum) were housed. But the main incentive and profit came from slavery.

Statia was well positioned in the middle of the islands and it had a good harbour, which was a freeport. It also sold arms and ammunition to anyone willing to pay and notably used these to support the American War of Independence. Statia became the most prosperous island in the Dutch Caribbean and it was dubbed The Golden Rock accordingly

Statia is very different to Saba. It doesn’t soar, but there’s still a formidably sheer cliff escarpment. Up-top is almost a plateau, sloping to the Atlantic coast. There are hills to the north, and to the south-east, the spiky outline of the Quill (Dutch for pit or hole) Volcano (about 600 metres). The island has an area of roughly eight square miles (six miles long and up to three miles wide). In cross section, it’s a saddle shape, depicted proudly on the nation’s flag. The flatter middle section is almost bisected by the runway of Franklin D Roosevelt Airport.

Quill Volcano

Quill is also known as Mount Mazinga. You can see it’s jagged cone from almost everywhere on the island, dominating the skyline. It must have been an awesome explosion. Fortunately, it was about 1600 years ago. The Quill is a national park, with attendant (steep and often slippy) hiking trails.

Saba or Statia?

As I’ve already observed, Statia is nowhere near as pretty as Saba, even utilitarian at times, with government offices and rows of gas and oil containers facing out to sea. There are still peaks and it’s picturesque in parts, with Prussian blue sea coves edged foaming white. But you can’t shut out the cylindrical tanks, peeking at the corners. There’s no uniform plan for building houses here. No Toytown. Instead, there are an assortment of dwellings, mostly timber, some concrete, some stone, ranging from ramshackle to highly decorated. There are still elements of gingerbread, with jutting eaves. And some are decidedly historic; as I had hoped, the diversity and colour does makes Statia more engaging.

Quill Gardens – Almost the Lap of Luxury

My hotel is definitely an improvement, however. It nestles beneath the Quill Volcano. I have a room with a huge sleigh bed, an enormous bathroom and a view across to the Atlantic coast. There’s a gorgeous, tastefully decorated terrace, with deft touches like blue lanterns. And a breakfast that features about eight dishes. Ah luxury.

At least, until the weekend. I chose this place, even though it is out of town, as it looked like a good place to relax and it has a swimming pool. But no, building renovation is in full scale, every day, all weekend. Even Sunday. I’m the only guest, so the owner deals with it by hustling me out of the way. Go snorkelling. Go hiking. Have a nice day!

Oranjestad

I’ve walked in to the capital, coastal Oranjestad (Orange Town, after the Dutch royal family, the same as the capital of Aruba). This is where my ferry landed. It’s rural round the hotel and the road is bumpy and unmade, to start. There’s a historic large boulder, painted with the name Big Rock. Apparently, it was spewed from the volcanic crater, on my left.

Oranjestad sprawls gently onto the middle of the saddle. Most of the population live here, in the residential and commercial hub. I wander past banks, schools, various shops and supermarkets, wares piled higgledy piggledy and spilling onto the pavement. There’s Duggans, the largest supplier, with rows of well stocked refrigerated cabinets. But it’s so warm outside, that all the doors are covered in condensation and you can’t see what’s inside.

It’s also hard to tell if the various restaurants and drinking establishments on the Fort Oranjestad Road are open – they’re dark and a little shabby. At the cliff edge, things get interesting. Merchants’ houses, restored Caribbean timber dwellings, churches (there’s a ruined Dutch Reformed church built in 1755, with a tower that can still be climbed), government offices, museums, the ruins of one of the oldest synagogues in the Western Hemisphere, a Jewish cemetery and a fort.

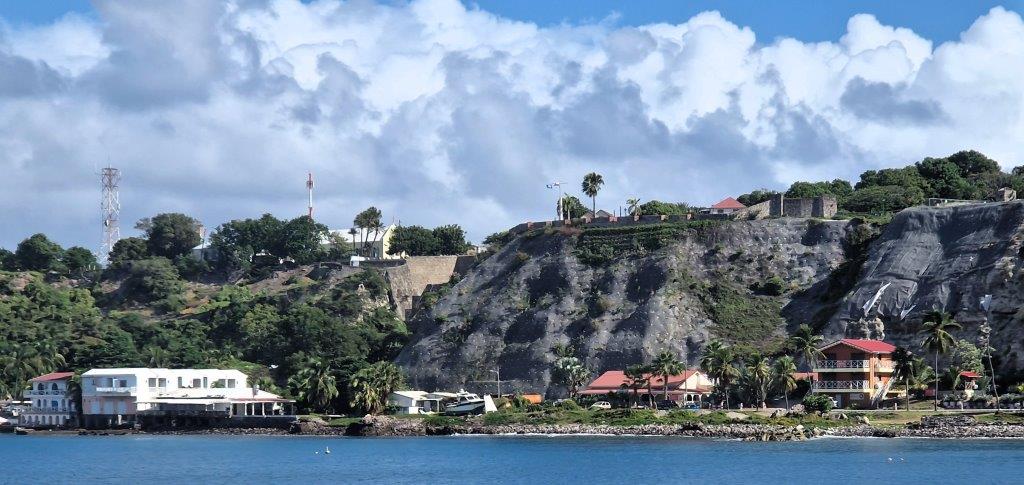

Fort Oranje

I think twice about entering Fort Oranje. This is the third fort in two weeks and I’m forted out. I’m going to change that phrase – it’s open to misinterpretation. I’m suitably fortified already. This seventeenth-century fort is as well built and maintained, as Brimstone, in nearby St Kitts, if smaller and lower down. It has cannons, intact bastions and a courtyard. The impressively steep slopes beneath have been reinforced and there are sweeping views along the coast. And some interesting history.

A plaque proudly proclaims this to be the first nation to recognize the independence of the USA, when they returned a salute from an American ship. The British were very upset and eventually declared war, the fourth Anglo-Dutch War. In 1781, Admiral Rodney turned up with a massive feet and forced Statia to surrender. Ten months later, the French arrived and took control. Then the Dutch won it back. (From the first European settlement in the seventeenth century, until the early nineteenth century, St. Eustatius changed hands twenty-one times between the Netherlands, Britain, and France.)

Oranjestad, Lower, Coast Road

Then, I drop down to the coast road. I follow the steep Old Slave Path down the cliff, (there are signs abjuring me not to let the goats through, no matter what they tell me), to find it is being renovated at the bottom; I have to scramble over a heap of rubble to get out. But there’s gin and a meal waiting for me down here. This is where the best restaurants and most up market establishments are. This road leads from the harbour, up to the north end of town and is lined with small beaches, which disappear and reappear over the years. Erosion is a big problem. The original wall defending the coast is several metres out, below water. The same fate, it seems, has befallen numerous colonial buildings along the path. Excavation and renovation has revealed an assortment of stone buildings, on both sides of the route. Existing plans are on hold, while they are all examined.

Maybe Not So Flat After All

Walking back to my hotel, I discover that the road from Quill to Oranjestad was a long, fairly gentle, descent. Returning is much harder work. I’m not encouraged to repeat the experience, especially as cars speed by giving little quarter. I’ve been told not to risk it at night. Which is fine, if you can track down taxi driver and don’t mind 10 USD a pop. I’ve also discovered that my hotel only serves dinner some nights and these are fairly random. So it’s town, or go hungry, or stock up at the supermarket, if you can find anything in the cabinets.

Exploring The Golden Rock

I’m back in Oranjestad again for a Round The Island Tour. Also along for the ride are a Dutch couple, normally based in Curacao, with the Dutch navy. Unlike my last guide, in Saba, taxi driver cum tour guide, Wade, knows his stuff and takes his time showing off the whole island, and trundling down most of the roads.

Round the Island is clearly a misnomer. There are roads on the flatter parts of Statia, but not into the hills at either end. and many are unmade. Where the streets are surfaced, the concrete is disintegrating badly. Wade says they were fine until building development expanded rapidly. Increasing numbers of parcels of land have been bought and built on over the years, with prices escalating accordingly.

Fort de Windt

South, to Fort Windt. (Yes, another one.) Fort de Windt at the extreme southern tip of Sint Eustatius about five kilometres south of Oranjestad, guarding the channel to St Kitts. It was one of 16 small forts built on Statia. It dates from 1756 and was named after its commander, Jan de Windt (not because it was windy there, though it is Dutch for wind). The fort never saw action and was abandoned in 1815. The two remaining cannons, on the restored fortifications, face across the choppy waters, to the loftier guns of Brimstone Fort on St Kitts.

South Statia

There’s little evidence of cultivation, other than market gardens. The sugar plantations, with their stone arched entrances and mills have long been abandoned and the ground is now a riot of flowering vines and creepers. Hugging the bottom of Quill, to the east, and on to the not quite completed, but very upmarket, Golden Rock Resort. The gardens in the resort are glorious, replete with exotic blooms.

North, across the island centre and round the airport, to a viewpoint in the hills, in the north-west. These are the smaller summits of Signal Hill/Little Mountain (or Bergje) and Boven Mountain. From here, Quill consumes the whole of the horizon.

Then, we drop down to Zealandia Beach, where the turtles (three species) brave the Atlantic rollers and come to nest. But not today. It’s wild, windy and strewn with weed. Swimming not allowed.

Snorkelling, Oranje Bay

I’ve been more or less thrown out of my hotel again, so time to go snorkelling. It was on my To Do List anyway. The lovely people at the dive shop, on the coast road, in Oranjestad, point out the reef, just off shore, in Oranje Bay and are very happy for me to leave my gear with them. They only run dive trips here.

The reef runs parallel to the shore, some of it inextricably mixed with the colonial, underwater ruins. It’s maybe a couple of metres at its tallest and perhaps two metres below the surface. It’s not the most thrilling of underwater experiences, but there’s bright yellow coral, some crimson strands and plenty of small fish, parrot fish, sergeant majors, weavers, puffer fish. The usual suspects. They’re congregating in twos or threes though, or hiding under ledges. No shoals. There’s also a cannon or two.

I’ve taken my underwater camera, but discover that I’ve brought it all the way from England with no SD card in it. So, after my swim, I toil up the Slave Path, to a Chinese supermarket, a glory hole containing every type of good that you can imagine in its depths and find a phone card I can adapt. It pours with rain. Back to the water and up and down the (murkier thanks to the downpour) reef again, taking pictures. When I emerge, (it’s one of those beaches where you scramble out trying to look dignified as the waves knock you over and your crotch fills with sand) I discover that I’ve had the camera on the wrong setting and most of the images are out of focus.

It’s raining again, so I wrap my towel round me and ask if The Barrel House Restaurant next door minds me coming in wet. The waiter says its fine, but it seems they thought I meant wet hair and are not so keen on me sitting there in my cossie. I’m not sure why – it is a terrace by the sea. But by now, all my clothes and towel are sodden and the rain buckets down again, blasting the terrace. So no-one objects any more.

Tot Ziens Statia

All good things come to an end. Though not the renovations at my hotel, it seems. Read more about the BES Islands here. Or follow any of my other adventures at www.suetravels.com.