Few people can claim a life as vividly lived and globally expansive as Andrew Warburton. From his quiet beginnings as a stamp-collecting child in Southport, UK — captivated less by the stamps than by the far-off lands they represented — Andrew’s life quickly took a path defined by adventure, resilience, and an enduring curiosity about the world.

His early love of geography and travel, inherited in part from a grandfather who took the family on rail journeys to places like St. Petersburg in the 1950s, laid the foundation for what would become a life of extreme travel: solo motorbike expeditions across Africa, leading rugged overland tours through jungles and deserts, and ultimately, confronting the harsh health realities of life on the road.

That personal experience — being both the traveler and the caretaker — eventually inspired Andrew to launch Blue Turtle, a company dedicated to natural, homeopathic treatments for tropical diseases like malaria, dengue, and hepatitis.

In this interview, Andrew reflects on the formative years that sparked his wanderlust, the hard-won lessons of leading expeditions through some of the most remote regions on Earth, and how a brush with debilitating illness in Indonesia unexpectedly set him on the path to pioneering alternative tropical medicine. It’s a story of grit, global perspective, and a deep commitment to wellbeing — especially for those living and exploring far from home.

Andrew, tell us a little about your early years in Australia and how your love for travel developed.

I grew up in Southport in West Lancs (UK) as an only child: quite happy in my own company and an ‘independent’ thinker from an early age. I was an avid stamp collector and inherited a fairly comprehensive collection from assorted aunts and uncles. The stamps themselves were of little intrinsic interest to me: I was interested in the geography and history of the countries behind them. My grandfather also had a love of travel and would take the family off to very unusual places long before travel was either packaged or easy. He took his family to St Petersburg and also to the south of France (via trains) in the late 50s…

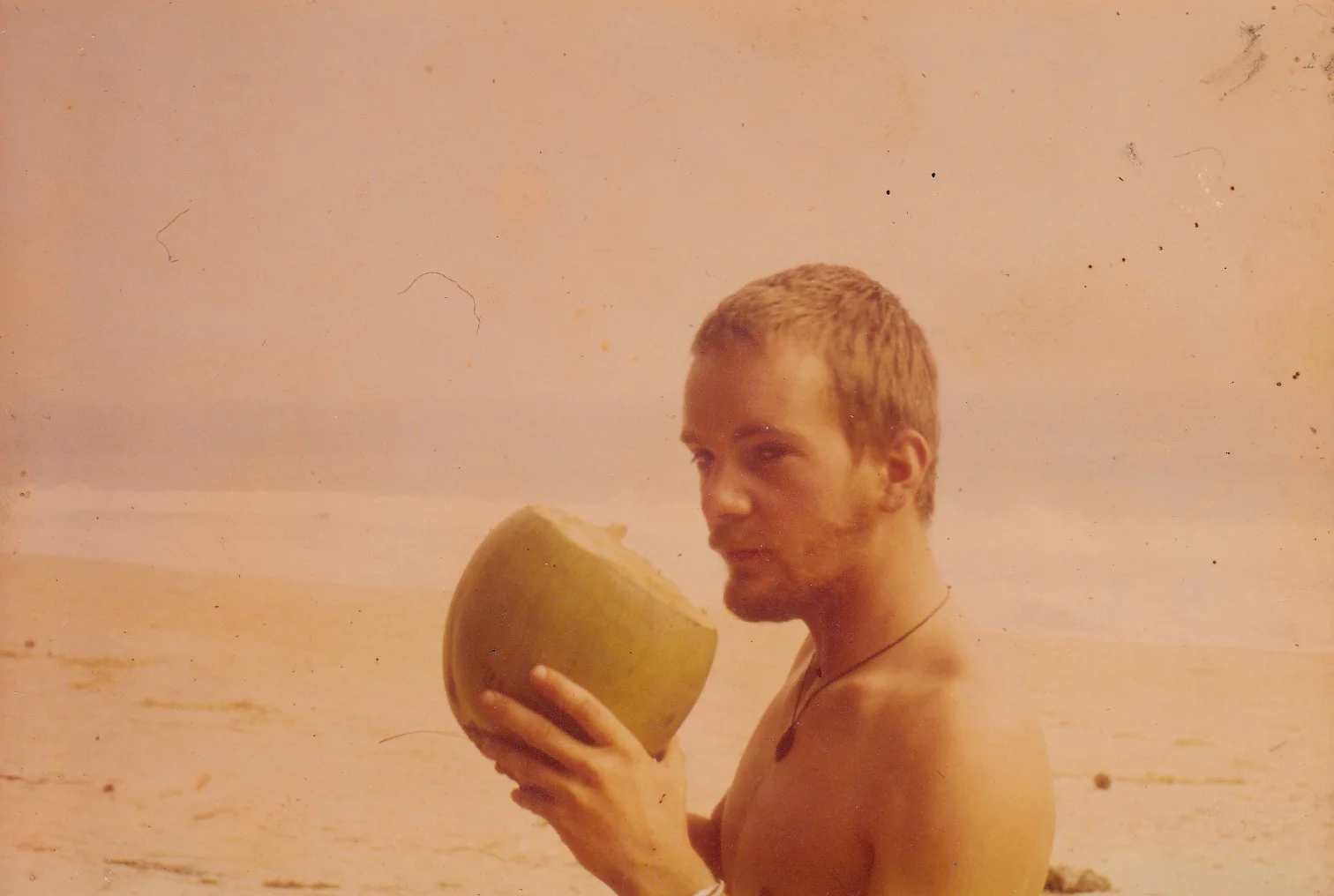

I hadn’t been further than Liverpool on the local commuter train by myself when I left for Africa on a motorbike. I’d made the decision some 18 months previously whilst driving into college in Plymouth to attend a course I knew I wasn’t altogether suited to. A friend had once remarked on a short drive to a surf break in S.Devon that the fluffy clouds in the blue sky indicated it was a ’traveling day’ and the wistful smile on his face convinced me that travel was something I needed to get into. Some months later (whilst still recovering from a fairly serious motorcycle accident) the sky indicated ‘travel..’ and by the time I’d arrived into town the plan was set: a motorcycle trip to South Africa and, hopefully beyond.

You spent quite a lot of time in Africa in the 1980s. Would you like to tell us a few of your memories from those times?

My time in Africa in the 80s can be split up into two sections: my motorcycle trip and then subsequent trips working for Exodus Expeditions and Okapi Africa.

My initial experience in Africa whilst traveling solo on the motorcycle through Morocco was one of almost constant harassment: very hard to be alone there. I would find myself riding until after dark and then sneaking into a field with my lights out to set up a tent in the dark and fall asleep exhausted. Somewhat vulnerable and constantly aware of the potential of theft I quickly learned to sleep with one eye/ear open: a habit that persists to this day. Traveling south from Oujda to the Algerian border at Figuig I began to feel Africa ‘opening up’ into much bigger spaces of ‘nothing’ (and no-one). It was wonderful: the Sahara beckoned!

I took side trips into small villages (eg Taghit) into the middle of the Sahara and, in addition to the incredible and timeless scenery, was astounded at the unconditional generosity and hospitality of the locals who absolutely insisted that I come to their house and avoid wasting money at hotels/restaurants etc. Given I had been warned by other travelers I had met in Europe on the way through as to how deceitful and treacherous Arabs could be this came as quite a shock and I freely admit to being ashamed that I’d bought into such prejudices without justification.

Sometimes fun things could happen too: I recall trying to get to the left (upwind) side of an oncoming truck somewhere south of El Golea in southern Algeria and tipped the bike over on the sand berm at the side of the piste. The driver saw this and stopped his truck to come over and help me pick it up. Alas, the bike had gone down on the side where I had a foam based tyre inflater strapped to the fork leg and something during the spill had triggered it. On seeing the bike being engulfed by a sea of sticky white foam, the driver’s eyes widened in shock and he fled back to his truck to disappear tout-de-suite into the distance: I and other devils were alone once more..

The motorcycle trip essentially qualified me to drive Overland tours. The notion was introduced to me by another colleague in Southport (UK) who reckoned I was more qualified than he was (he had a truck license: I had passport stamps) so I applied to a few companies to get into the overlanding industry.

Overland Expedition leading is great fun but it’s also a finely balanced act between professionalism and hedonism. The passengers like to describe themselves as expedition members but the reality is they really feel and want to be on holiday: sometimes it’s hard to get the passengers to take things seriously.

Algeria, April 1981

I recall an incident which was both funny but deadly serious at the same time. We were driving up through southern Tanzania from NE Zambia and the terrain was pure Daktari: small rolling grassy hills with baobabs casually strewn across the valley floor. Ahead were some youthful Massai tending a large herd of goats: I slowed up some.

Suddenly one of these young goatherders struck into a fierce defensive stance and held up the truck with his spear locked into the instep of his foot and the point held rigidly towards the truck: wtf? I braked sharply and dropped to 2nd gear lest I run him over. In a flash he was at my driver’s side door and thrusting his 8’ spear in through the open window at my head!.

Not wanting to have my ears pierced so early in the day I leaned across the gear box selectors and floored it. Alas, being only in 2nd there was only so much flooring to be had and I needed to bob up off the gearbox to change gear: not easy with a spear repeatedly being thrust through the window and thudding upwards into the roof.

The cab passenger steadied the steering wheel whilst I used my free hand to wind up the window and then managed to sit up briefly to change into 3rd and go a bit quicker, all the while the spear bouncing off the window glass: I prayed it wouldn’t break. Meanwhile all the passengers up top and in the back were roaring with laughter. We were out of there and I was sharply cognisant of the fact we weren’t watching a wildlife documentary on TV: life was real and it wasn’t necessarily predictable or friendly..

What were some lessons you learned from that? (hint: you can introduce the need for health, safety etc)

Afterwards I heard that someone had been using a telephoto camera lens at a distance to get a better look at the goat herders in action who, in turn, thought their pictures/souls were being stolen: I was the driver and therefore it was all my fault…

Whilst I had always assumed the job came with a high level of responsibility, this event brought it home to me, quite starkly, that I was responsible for anything and everything that the passengers got up to at a moment’s notice. Despite their advance preparations (or none!) I was directly responsible for the heath, safety and wellbeing of 20 or so people (all strangers to each other) 24/7 for six months and to deliver them from London to Harare (or vise versa) along a mostly predetermined route and schedule: easy when you say it quickly.. Although ostensibly an ‘expedition’ the passengers were led to feel as though they were embarking on a holiday: travel brochures can be a curse..

Somewhere in the jungles of Central Africa, 1991

Routines were established and we divided the pax up into 7 groups of 3 and these became the cook groups. It was essential to have 7 groups, else you’d soon lose track of what day of the week it was: quite important when it takes 4 weeks to cross Zaire and you only have 1 month visas.. Shop stops were invariably in the mornings (we’d ensure camp areas were found 30-40km before a sizeable town); wood stops after lunch though before the 4 o’clock stops (beer!): no one was allowed to use an axe after drinking beer..

So, what experience do you have in terms of medicine for frequent diseases one may get while travelling?

I knew from my earlier trip via motorcycle that a healthy trip was more likely to facilitate a happy trip and I’d heard how other overland trips had collapsed into survival ordeals by virtue of having too many of the ‘expedition members’ sick at the same time so I made sure to inculcate a culture of safety and mutual health awareness at all times.

I led by example and ensured I was fully covered up by 4pm each day: long sleeved shirt, jeans, socks & shoes: plenty of mosquito repellent. I’d had malaria before and wouldn’t wish it on anyone: I wasn’t going to get it again. Early on in the trip, usually around the first campfire (or hotel bar if still in Harare), I’d discuss health matters and ask what antimalarials the pax had brought with them: the range was actually quite incredible with some bringing meds along that had long been banned in other countries (eg Lariam) and others having pills that were no better than aspirin..

We also discussed their individual side effects: some permanent. I couldn’t exactly tell them so soon into their ‘holiday’ that their assorted pills were mostly useless so I emphasised the virtues of avoiding being bitten in the first place.

In due course just about everyone got malaria, however, due to increased prudence around clothing and repellent, we had it to lesser quantities than on other trucks we came across (ie fewer people sick at the same time).

Tell us a little bit more about your medicine company, Blue Turtle.

After a few overland tours with Exodus I took a break of 18 months or in Australia and coincidentally entered the mining industry as a sample prep technician (lowest rung of the ladder). On my return to the UK in ’91 I elected to do ‘one more overland for the road’ before going back to college to study Mineral Process Engineering (metallurgy).

After completing that and following a brief stint on a gold mine in Tajikistan dating back to Alexander the Great, I took on a role in Indonesia for a geological exploration company who, since the Bre-X fiasco, needed a western engineer to represent their laboratory efforts. Whilst there I managed to get myself badly bitten by a dog and, despite getting a follow up booster for rabies, started to develop some worrying symptoms.

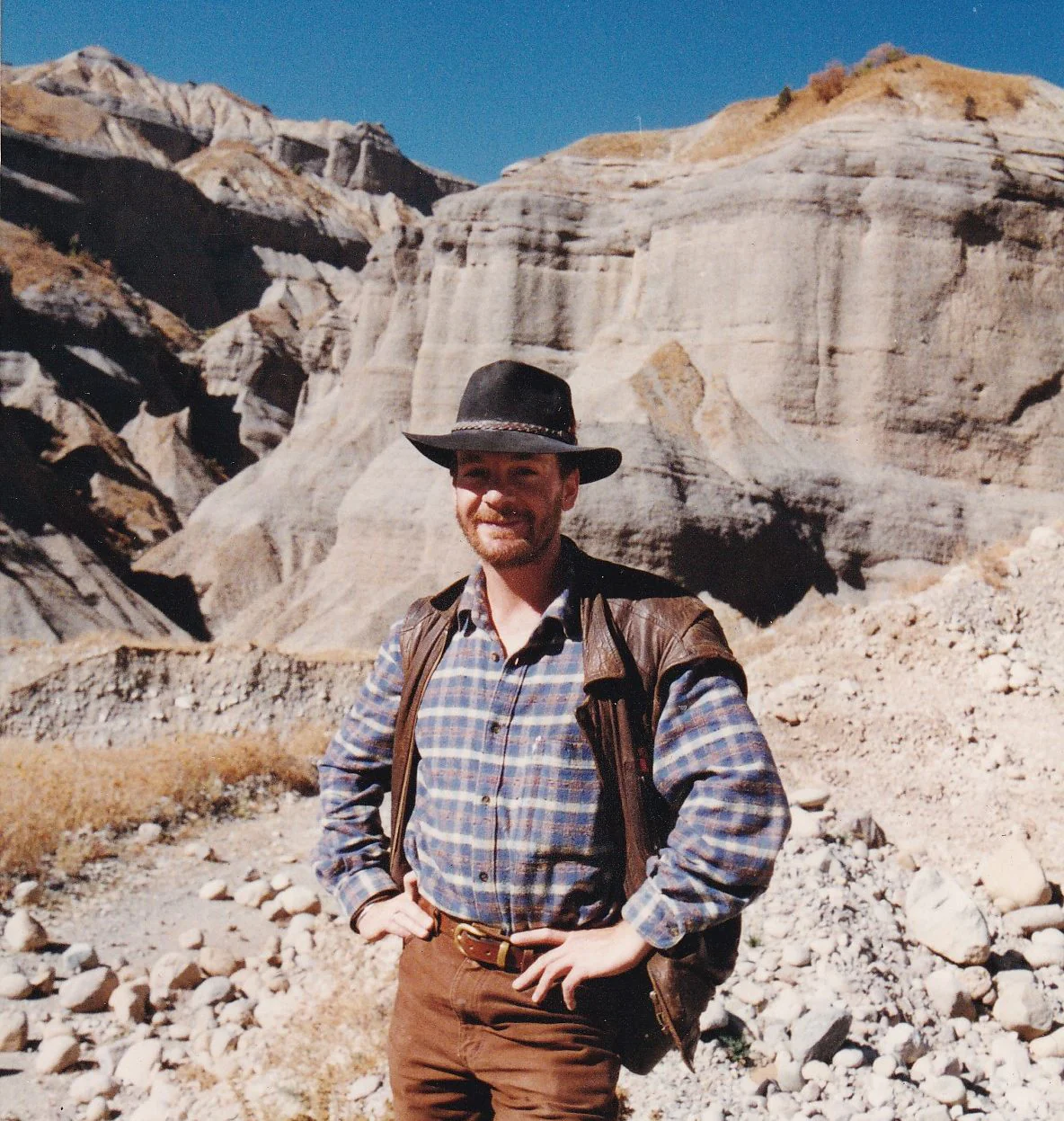

Tajikistan, 1995

In addition to sporadic twitching, I had developed a form of acute viral arthritis which was progressing from my extremities by at least one joint per week: the way things were going I’d be in a wheelchair by the end of the month. The AEA medical people in Jakarta determined it couldn’t be rabies directly as I’d lived too long since being bitten: there was little/nothing they could do and so wished me well.

Some colleagues from a local tin mine took pity and put me onto some naturopathic/homeopathic people in Yogyakarta who promptly diagnosed liver poisoning (from the rabies booster) and dispatched a remedy to treat it with. It arrived within a couple of days and was simple enough to take: within 3 weeks I was ~85% cured and within 3 months I’d largely forgotten I’d been bitten by a dog at all. Given the likely prognosis beforehand this was little short of miraculous.

Spurred on with the success of this treatment I asked what they might have for malaria and warned them I’d had malaria before so knew the subject matter firsthand. This excited them a little as they mentioned I’d have to use their remedy, Demal200, to undergo a full malaria detox routine to purge my liver/system of residual malaria parasites before going on to use it as a preventative as otherwise the prophylaxis dosage rate might only be sufficient to awaken the parasites likely to be dormant in my liver.

I advised I should be able to skip this as, after being treated by the best physicians at the Tropical School of Medicine in Liverpool, I’d been given the ‘all clear’ in respect of Malaria. That said, I was warmed that, should I ever present to a GP with a feverish ailment such as a bad cold or ‘flu virus then I must warn the GP I’d previously had malaria. Once I said this aloud it struck me with force how ridiculous I sounded and that I still had malaria: the logic was obvious..

I was warned that the malaria detox protocol using Demal200 generally involved some mild malarial response symptoms to some 10-15% strength of a full malaria attack and take a few hours to complete. I followed the instructions without any real expectation of anything given I’d not had a recurrence since I received the ‘all clear’ in ’85 and was quite astonished when, after 15 mins of 5 min interval doses suddenly felt as though I’d been whacked with a brick..

I duly dropped back to the 25-30 min dosage interval level and rode the treatment out for a further two hours after which no further response symptoms could be provoked: I continued for a couple more hours (as directed) just to be sure the treatment was complete: so far so good. The next day I repeated the initial 5 min dosage regime for an hour just to be sure my liver wasn’t hanging on to any ‘secrets’.

After I’d completed the detox routine I recall feeling quite tired/drained and even a bit hungry. I was warned this was likely to happen and was a good sign that the treatment was complete: the immune system and healing process burns a lot of energy and hence the fatigue and hunger when it was complete. A couple of days later the results of the treatment became more readily apparent to me: I felt fantastic! My thought processes were clearer, my eyesight sharper and energy levels at an all time high. It was akin to taking off a heavy backpack after a long hike: I was walking on air!

Impressed, I resolved to look into this further when I ultimately left Indonesia and returned to the UK as the effects of the SE Asian financial crisis of ’98 took hold and the exploration projects around the archipelago ground to a standstill.

The guys who make the remedies, an elderly team of French homeopaths now based in Australia were happy for me to represent them as long as they could maintain their distance from the public eye: they were getting on in years and didn’t need excessive media or other attention.

I started off with ~80 bottles of Demal200 and sent many of these out as samples to drivers I knew in various overland companies and also to assorted safari camps up and down East Africa. Following up again after a month or three the excitement and orders for many more told me I had a burgeoning mail order business on my hands.

At the time ‘ninja turtles’ were popular so I simply reworked this to Blue Turtle (connotations of nature and eco-friendliness). The internet was still quite young in 2000 and a domain name could be had reasonably cheaply ($50) A govt. grant to buy a laptop helped me develop a website (currently on it’s 4th iteration) and the rest is history.

Following on from the early success of Demal200 (which has actually been around since the late 70s though only in Indonesia and to those in the know..) I added some of the lab’s remedies for other tropical diseases: typhoid; hepatitis and dengue fever (for which there is no conventional treatment/prophylaxis).

What is Demal200 and how does it work?

Demal200 is an all natural homeopathic remedy which works to strengthen the immune system and trigger it to respond to and kill malaria parasites. The parasite is able to change its surface coating protein in order to mimic the blood and thereby evade the immune system. Demal200 utilises potentised phosphorus to paralyse the parasite’s ability to change it’s surface coating protein long enough for the immune system to see it and respond. Other components of the remedy cause the production of appropriate antibodies primed to latch onto and fight the parasites before they have time to reproduce. In this way Demal200 behaves as a vaccine (which needs to be taken daily).

Dispensed from a small pump action bottle, Demal200 is taken as a spray under the tongue 2x per day. It is safe for all the family to use: there are no side effects and it even tastes good (kids love it!)

Similar to Demal200 is Dembarah200 which works in a similar manner to Demal200 but works against the same family of flaviviruses that causes Dengue Fever. Other than Dembarah200 there is no conventional treatment (other than blood transfusions) for Dengue Fever.

What are some of the challenges and opportunities of being involved in the business of tropical medicines?

Homeopathic medicines work in a different way to conventional allopathic treatments which rely on the principle of using a poison to kill an unwelcome bacteria/virus/parasite. Homeopathic treatments act by mobilizing the immune system to target and kill the offending invader: a far healthier approach.

To date, and in order to protect their hegemony, no medical authority has published any criteria against which homeopathic medicines can be measured for efficacy. From a marketing perspective, one of the main and obvious challenges is how to persuade someone to take something that is unapproved for something that could potentially kill you. On this basis almost all of our sales and business growth has been based on word of mouth.

Until only a few years ago much of our business was with overland companies and also missionary groups in all far flung places of the world from Africa to PNG and beyond. More recently (and especially since Covid) more naturopathic (and some GP) practitioners have come on board from many parts of the world to source our treatments for Long Covid, CFS/ME etc and also to pass the word as necessary.

Can you give us some success stories of people who have used your products while travelling and come back to thank you?

That’s a tricky one: there have been so many! We currently have about 250 such stories on our guestbook page. I guess a few still stand out for me;

Irene Gleeson in Kitgum (NE Uganda) who sheltered many hundreds of children against the child soldiers of the Lords Resistance Army. She had been running an orphanage there for 13 years and her health declining rapidly until she came across Demal200 from one of her visitors. Irene received the Order of Australia for her selfless work in Africa.

Another, a chronic hep-B case in an elderly resident of Belgium sent a handwritten note as follows (which I read whilst having breakfast).

Hello Andrew, After so long, I finally heard my doctor say the words: “You are healed”.. I could not believe my ears, so I asked him again and he repeated the same words. I had almost given up hope that that would ever happen for me. But I had to keep up with the treatment because I know it was helping me fight this virus, and it worked. I thank God for helping me come across your website on the internet and getting in touch with you.

I thank you also for your kindness, as you sometimes gave me the products free. I really do appreciate that. I did ask my doctor to make another test, just for me to be sure, but he refused, because he saw no need to test again, seeing the result he now has, says I don’t have the virus any more. Two years ago, when the test showed that the HBS had gone down to 8, he was still warning me that I was still contagious to other people. So I have to accept and believe the result to be good.

Thanks again Andrew. It was a long ride for me, but I am glad I stuck to it, and it has finally paid off. It was worth it. I will refer and make mention of your WebSite to others when ever possible, cause I know and believe the medicines work. Feel free to send me any new news or information you may have in the future. Take care and God bless. Truly Grateful, Agatha. I have to admit I was reduced to tears over my cornflakes with this one..

Possibly of more immediate relevance to NomadManians was some feedback from our #25, Janie Borisov who reported the following:

I used to get malaria every time I went to West Africa. Not since I’ve discovered Demal! I’ve been back to Africa and other malarial areas many times since and never been sick again. I also successfully got my old malaria out of my system, so no more sudden spells. I’ve recently discovered Dembarah200 and was equally impressed, getting my old dengue out and not getting sick despite myriads of mozzie bites in Congo, Gabon etc etc.

Thank you for making a huge impact on my health! Janie also lives here in Adelaide and so we’d occasionally meet up to chat about our respective travels. It was Janie who put me onto NomadMania a couple of months ago and I’m really grateful for the contact and opening my eyes as to the scale of people traveling for reasons other than family/work etc.

Check out Blue Turtle products here.

Coming back to your travels, what is still high on your bucket list in terms of places you’d like to go internationally?

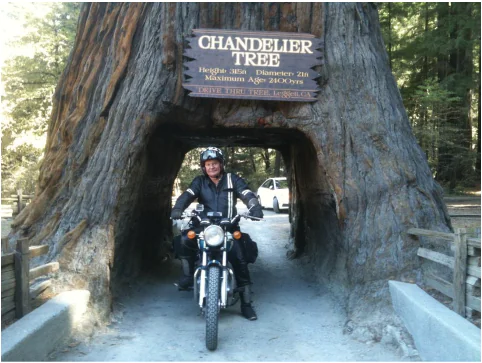

I’d really like to travel the west coast of South America: motorcycle or 4WD perhaps. More realistically (for me) I’d like to go back to the USA and continue to travel there (old car or motorcycle). Some years ago I bought an old Triumph motorcycle (’71 Tiger 650) in Dallas and opted to collect it in person and tour the western states on it for a couple of months. I had a ball: Americans are so friendly and hospitable.

Also, unlike Australia, the scenery changes completely every couple of hours and each state is so different from it’s neighbour. I toured from Dallas up through to Colorado and, via Vegas, on to Montana before coming back down the Pacific coast all the way to Los Angeles from where I shipped the ‘bike back to Australia some 2 months or so later. I’d like to go back and explore the southern states next time: Alabama/Tennessee; the Everglades of Florida and the Carolinas

And what aspects of Australia would you like to still explore?

Now this is a tricky one.. I love my road trips (4WD car or adventure motorcycle) through the outback and I’ve seen a lot of Australia. My day job as a consultant mine metallurgist/engineer still takes me to strange places I know little about and I’m always interested in the local histories of those places which I wouldn’t ordinarily become aware of.

The aborigines tend to get a bad press in many areas though I’ve come across many from very remote communities who seem very different from those in the larger towns who have fallen into bad habits. The ones I’ve met (hitching etc) from the more remote communities seem very much alive and connected to the country around them. They clearly have a lot to give if only the right questions are asked.

I like to travel the outback as often as possible. The emptiness lets my thoughts wander and new ideas come through..

What’s your suggested ‘hidden gem’ in Australia that not many people know.

The biggest problem with Australia is it’s size: it’s so big that you need longer to see everything and getting around is expensive. Rather than to arrive in Melbourne, hire a car/van and drive up the East coast to Cairns in far north Queensland to leave 6 weeks later I’d suggest flying into Brisbane and taking the train to Townsville to hire/buy a van there and then start heading west.

Be sure to visit the pub at McKinley in W.QLD as this is the ‘Walkabout Creek’ pub used in the opening scenes of the Crocodile Dundee film. From there continue west through to the Kimberley and spend the bulk of your time there as this is also ‘Crocodile Dundee’ country and evocative of the outback Australia in western consciousness. When leaving Australia you could then sell the van in Darwin at a profit!

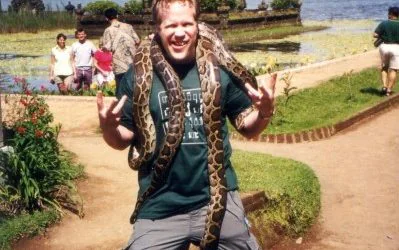

Croc refuge and park Nr Townsville QLD

What do you like best about NomadMania?

I haven’t actually been a member long enough to explore all of the attributes of the site though love that it feels like a ‘club’. Looking into the various countries’ profiles gives an insight as to how many NM members have traveled there which of itself can also give an indication of how remote/sophisticated those places are (or how expensive!!).

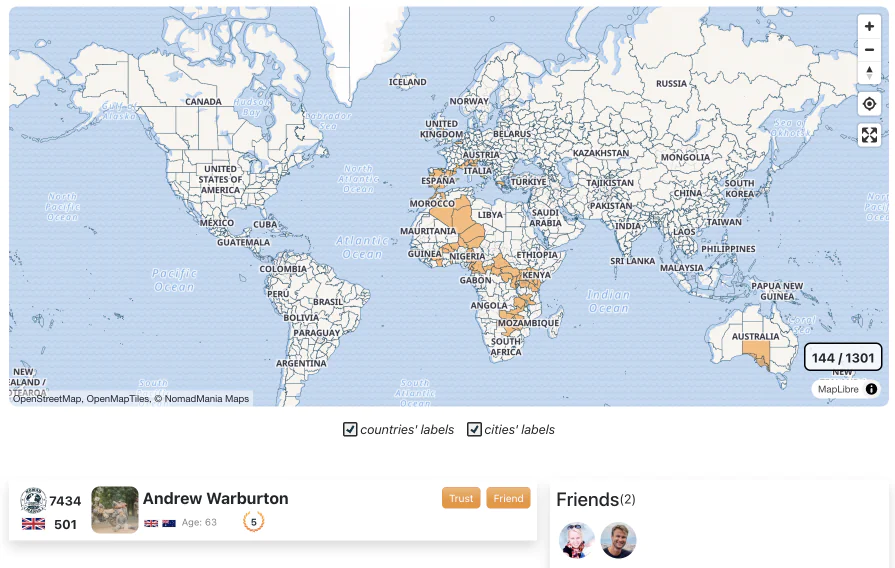

Andrew’s profile on NomadMania

Finally our signature question – if you could invite any 4 characters (real people or fictional from any period of history) to an imaginary dinner, who would you invite and why?

Gosh, another tricky one…

I’ve always liked rail travel and it’s an efficient way of moving people around. Also, there is far more scope for social interaction on trains than there is in cars (of which there are far too many in this world).

I’m also fond of Victorian architecture so I guess one of the invitees has to be Brunel. Another might be Margaret Thatcher, I was always intrigued with her before she came to power: anyone who had the power to irritate so many people so much even before winning office had to be good. I wasn’t disappointed. She’ll be needed to help put Brunel’s grand plans for more railways and bridges into action.

Another invitee has to be Ronald Reagan in order that I can hear his and Margaret’s reminiscences (together with his legendary after dinner jokes). Finally, Michelle Pfeifer (just because I’ve always liked her and I can)!