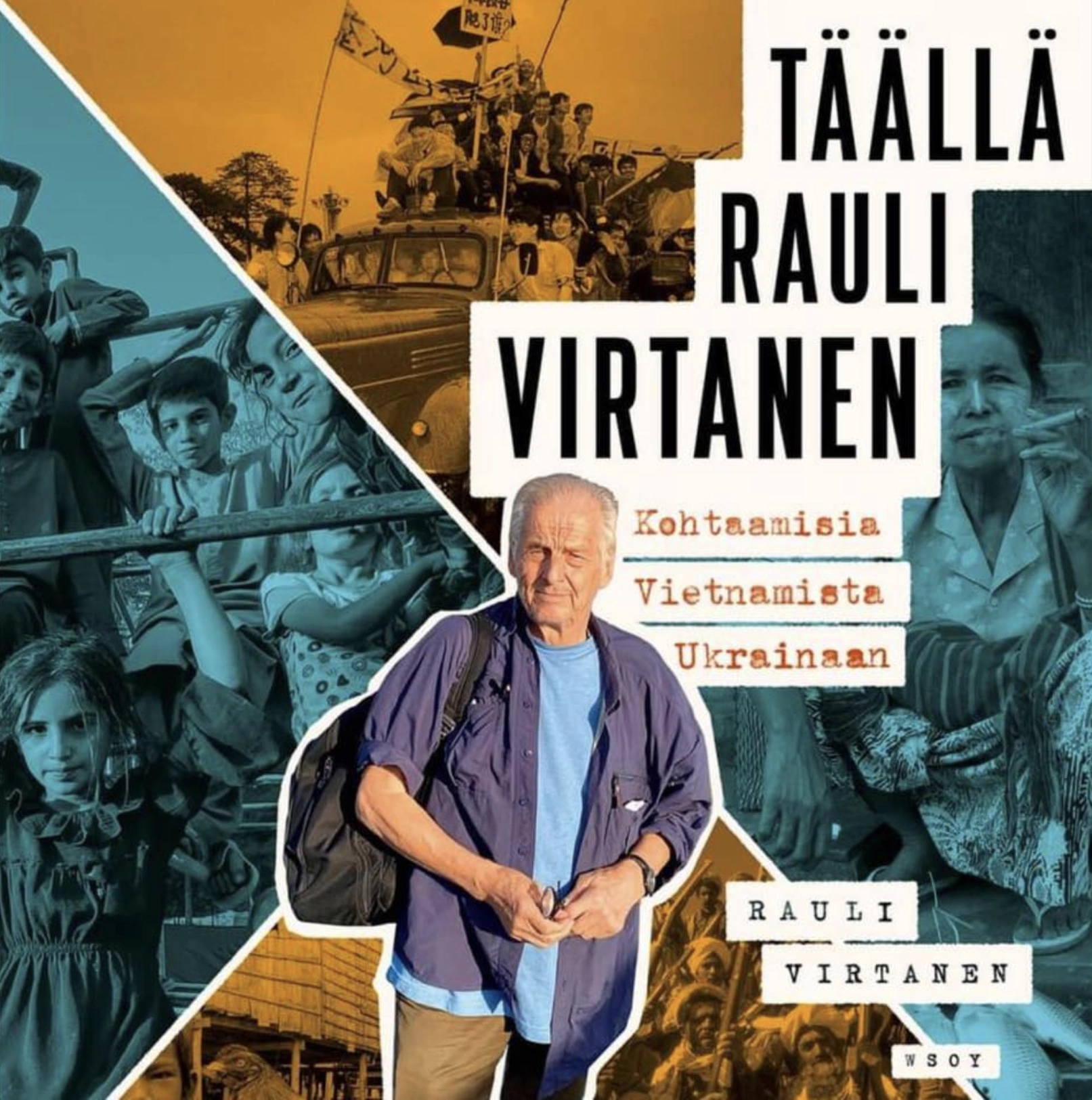

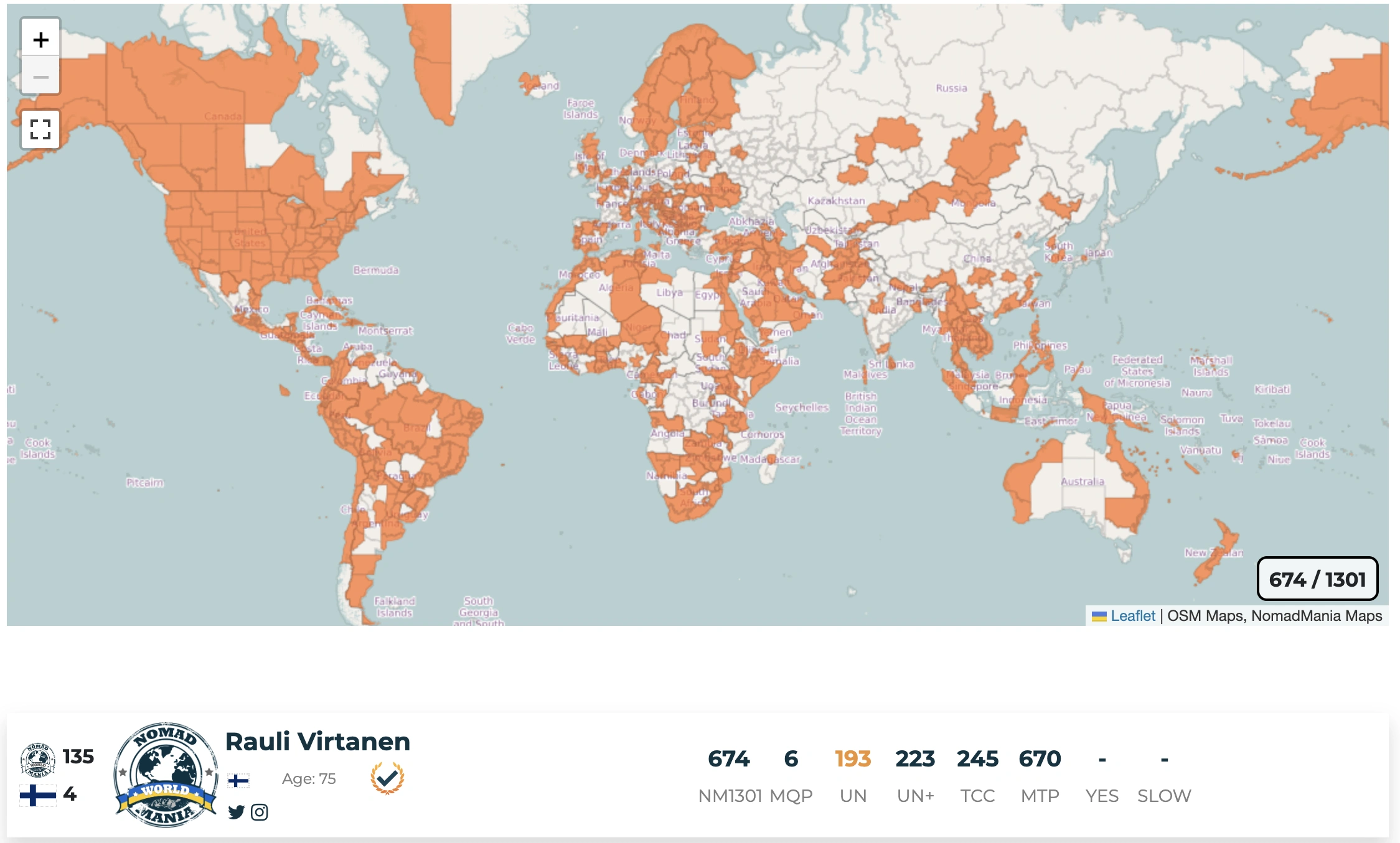

Today, we’re honoured to introduce a guest who isn’t just remarkable but may well be a record-setter: Rauli Virtanen from Finland. Believed to be the first person to have legitimately visited every country on the planet, Rauli’s journey goes beyond mere globetrotting.

For the past 50 years, Rauli Virtanen has distinguished himself as a renowned journalist specialising in conflict zones. His work uncovers the darker facets of world history, offering invaluable perspectives often missing from mainstream narratives. As if his life weren’t already a tapestry of incredible experiences, Rauli has just completed his latest book, “From Vietnam to Ukraine,” which is slated for publication.

We’re thrilled to have the opportunity to delve deeper into his astonishing life and discuss his new book. It’s a real pleasure to have Rauli Virtanen as our guest today. This interview is available in video form on our Youtube Channel.

You’ve lived in Helsinki for a large part of your life. Let’s go back to the 50’s or 60’s and let’s look at both Finland and Helsinki and your life. Can you tell us a little about how things were back then.

Well, I grew up in Lahti, the fourth-largest city, and part of my childhood was spent in the countryside. Then I went to high school in Lahti. At that time, Finland was not very international; we were recovering from the war. But Finland was quickly modernising and becoming an industrial society after being an agricultural society. So that’s one of the few things that came out of the war.

Lahti has been my hometown, and the most important reason why I am still traveling is thanks to my teachers. My first teacher was very enthusiastic about nature and geography, so I became interested in the world. My Finnish language teacher was reading my articles and what I was writing about, and advised me to become a reporter. So, I ended up reporting in Lahti more than 50 years ago.

How did you jump from general reporting to war reporting?

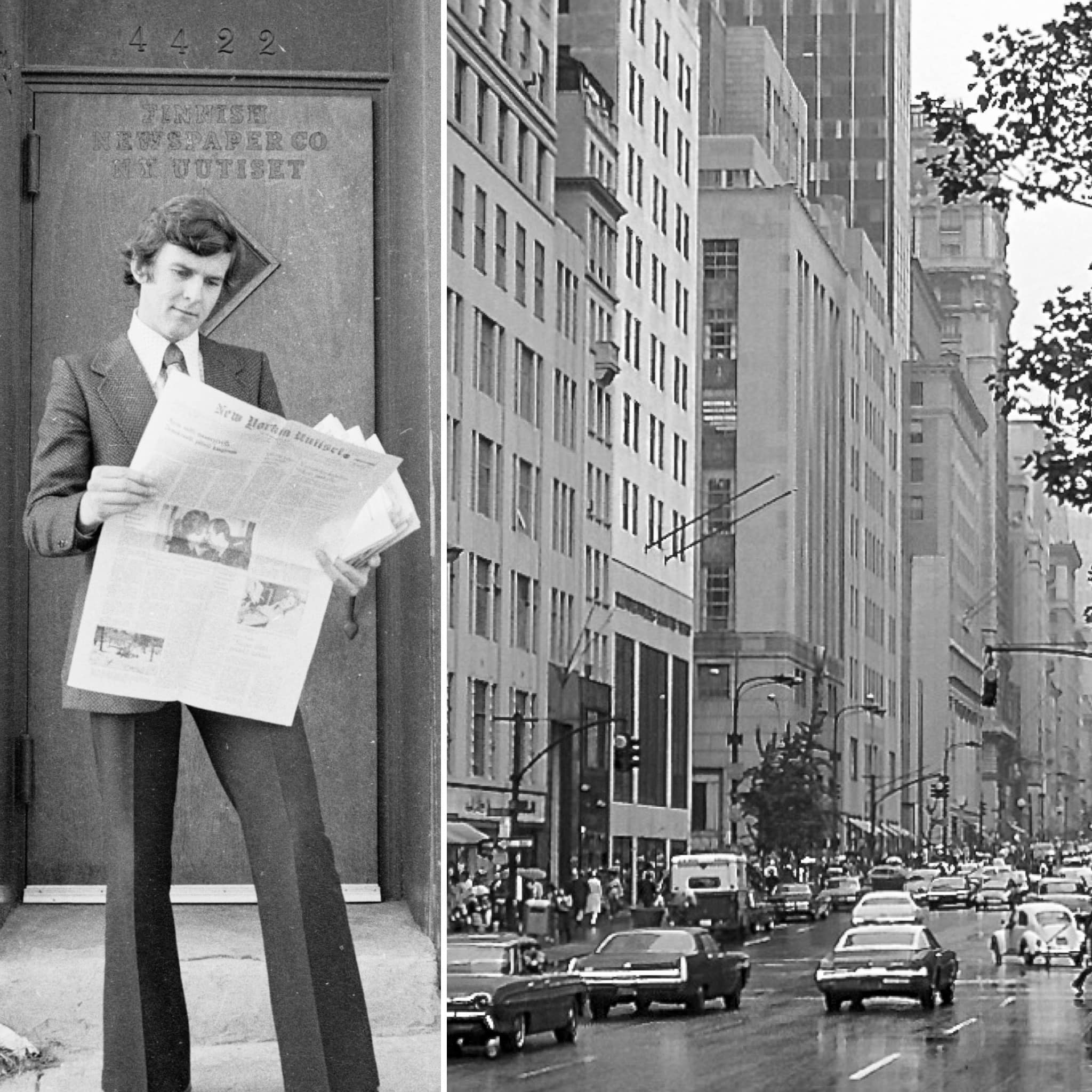

I was interested in foreign lands and countries, and at my first job with a newspaper, they told me to focus on Latin America because everyone else was concentrating on the Soviet Union, United States, Germany, etc. So, I took it very seriously and noticed that I was in Finland writing about these countries but had never been there. So, I took a cargo ship from Finland to Rio de Janeiro and embarked on a 10-month backpacking trip to South America and North America. During that trip, I was sending articles to provincial papers in Finland.

Afterwards, I counted my finances and noticed that I had managed to earn $100 each month, and with that money, I was moving myself forward from Brazil to Alaska, mostly through hitch-hiking. So that was a big experience and during that trip I learned to trust people, I learned to become less shy and more open and that, if I wanted a place to sleep or something to eat, I had to open my mouth and try my Spanish or Portuguese or English.

Shyness seems to be one of the characteristic of the Finns so I see you differentiated yourself from that. What year was that, Rauli?

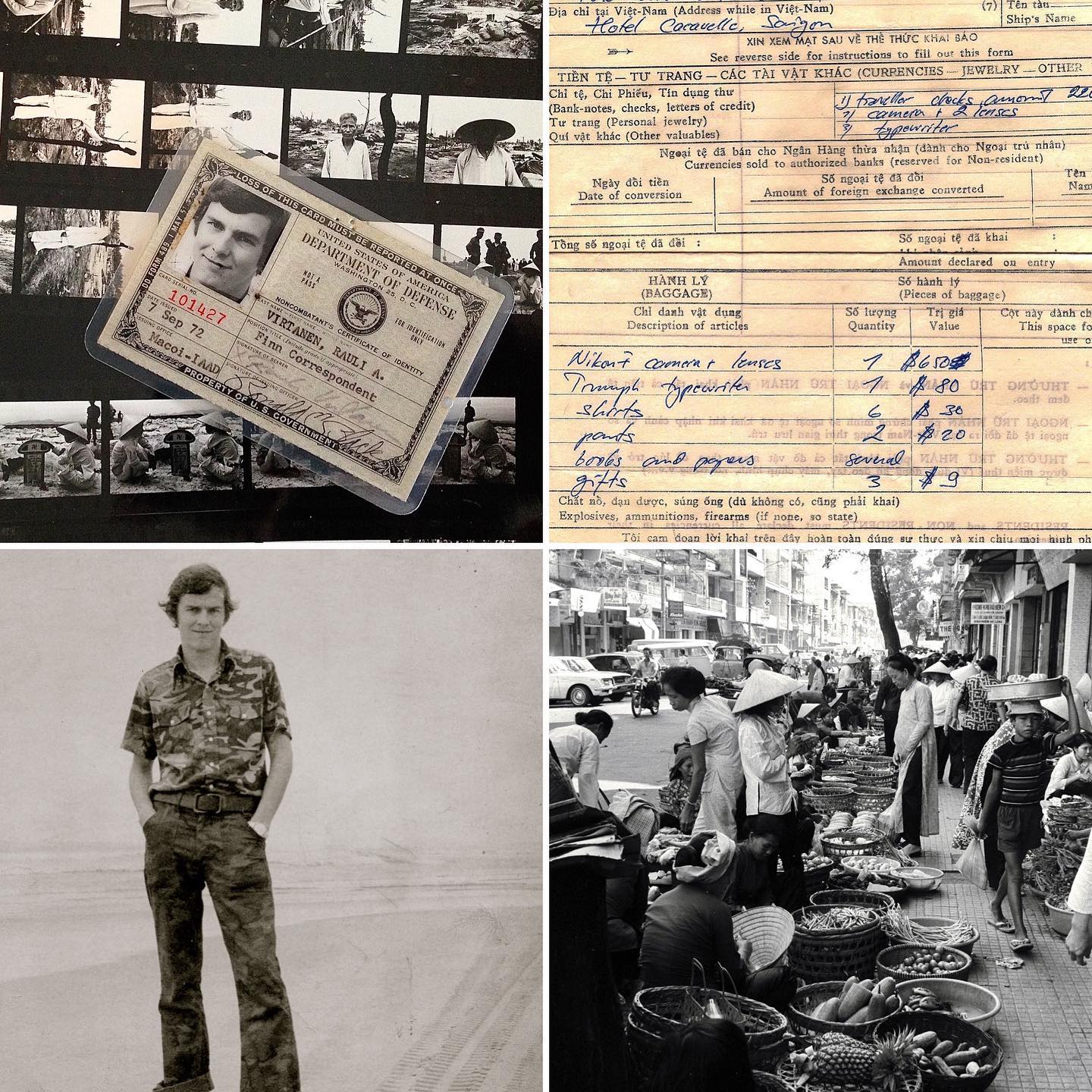

Yes, that is correct. That was in 1970 and 1971. After that, I applied for a job at a big Helsinki newspaper at the foreign desk. I then moved to Helsinki. After a few months, I told my editor-in-chief that there is a war in Vietnam and I would like to go there and cover it, and for some reason, they accepted my idea.

So that was my first war, in September 1972. I flew to the south of Vietnam and travelled with the Americans, and of course, I had to be embedded with their military in order to fly in their helicopters and planes. At the time, I was interested in the victims and also the causes of the war, so I visited refugee camps, hospitals, funeral homes, etc. So that’s how it all started.

In your 50-year-plus career, you’ve probably faced an incredible amount of situations. Could you maybe give us a couple that really stand out? Things that have really stayed with you?

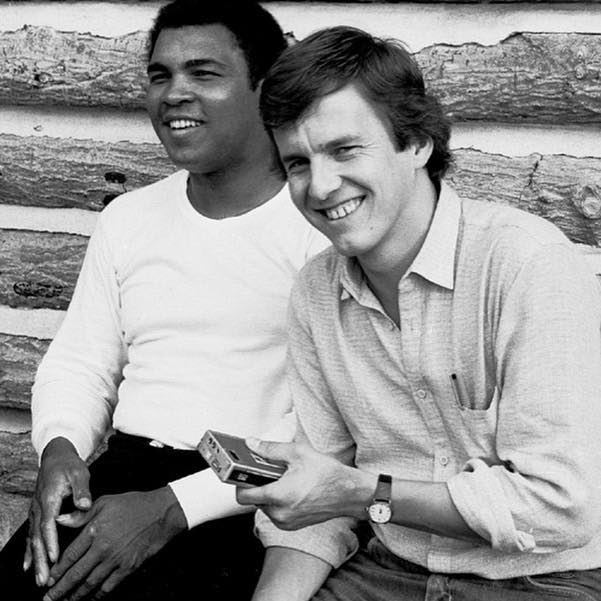

Well, there are many historical situations in my new book about the Tiananmen demonstrations. I was in Bucharest, Romania, in 1989 around Christmas, witnessing the Romanian revolution. I also witnessed the 1979 Managua, Nicaragua revolution, and then, of course, meeting people like Nelson Mandela, which was one of the greatest honors. To sit down with him, interview him, and travel with him to different places was an honor. Also getting to spend the day with Muhammad Ali, Yasser Arafat…

I always emphasise that the most important and heartwarming events are just meeting the locals in developing countries. It seems that the more poor they are, the more hospitable they are, so that has given me a lot of strength and optimism for the future.

You’ve seen so much pain, misery and devastation. How do you deal with this on a psychological and emotional level firstly while you are there and then afterwards when you mentally process it?

Well, there are, of course, times when you end up in very dangerous situations and you say you’ll never do it again. However, I always want to emphasize that foreign correspondents do not stay for too long, and our fixers, people who help us — for example, in Ukraine, like Orest — stay there and are risking their lives 24/7. We very seldom hear stories of journalists acknowledging the help of people like this.

So sometimes I get frustrated when, in Western headlines, we hear of foreign correspondents being hurt or killed, but we hardly hear about what is happening to the brave journalists of Mexico, the Philippines, or Russia who are being killed. In that case, it’s not fair.

To answer your question, of course, you have to protect yourself mentally. In my profession, the most important warning is: do not become cynical. If you become cynical, then you have to leave. I think in my case it has been fairly positive, but I still would like to remind people of what those in poor countries that are in conflict situations are going through.

You mentioned that Nelson Mandela is one of the people who impressed you the most. Why Mandela? What was it about him that has really made a difference?

Basically, the non-bitterness, his gentleness, friendly approach, and sense of humor are what I really admired about the late Nelson Mandela. Unfortunately, now in South Africa, things are not going well. There’s still economic apartheid, and we obviously know about the ANC’s corruption, so I wouldn’t say that he is resting peacefully if he knew about this. In today’s world, we need more Mandelas. It’s very difficult to find another Mandela in today’s world.

Okay, let’s turn to your writing. So obviously as a foreign correspondent, you have written many articles throughout the years but you have also written some books. Tell us about your older books – what they were about and why you wrote them.

My first book was in the late seventies when I had traveled to Latin America, which was the first continent I specialized in, so I went there again and again. Actually, now in September, it’ll be 50 years since the Chilean military coup when Pinochet took power there. I left for Chile from New York the same day I heard the news, September 11.Then I witnessed the Dirty War in Argentina and went to Cuba, and of course, visited all the Latin American countries very early on, including Caribbean countries. So I wrote a book about Latin America in the late 70s. I’ve also written a book about Finns, my countrymen.

The book covers Finns as peacekeepers and their history, basically since 1956 when the Finns were part of the UN forces in the Suez Canal, up until their later service in Afghanistan. They’re not serving there anymore, of course, but some Finns still participate in peacekeeping operations.I’ve been writing another book about the development cooperation between Finland and those who are the pioneers in development cooperation, focusing on their work in Tanzania from the early 1960s and 70s until today.

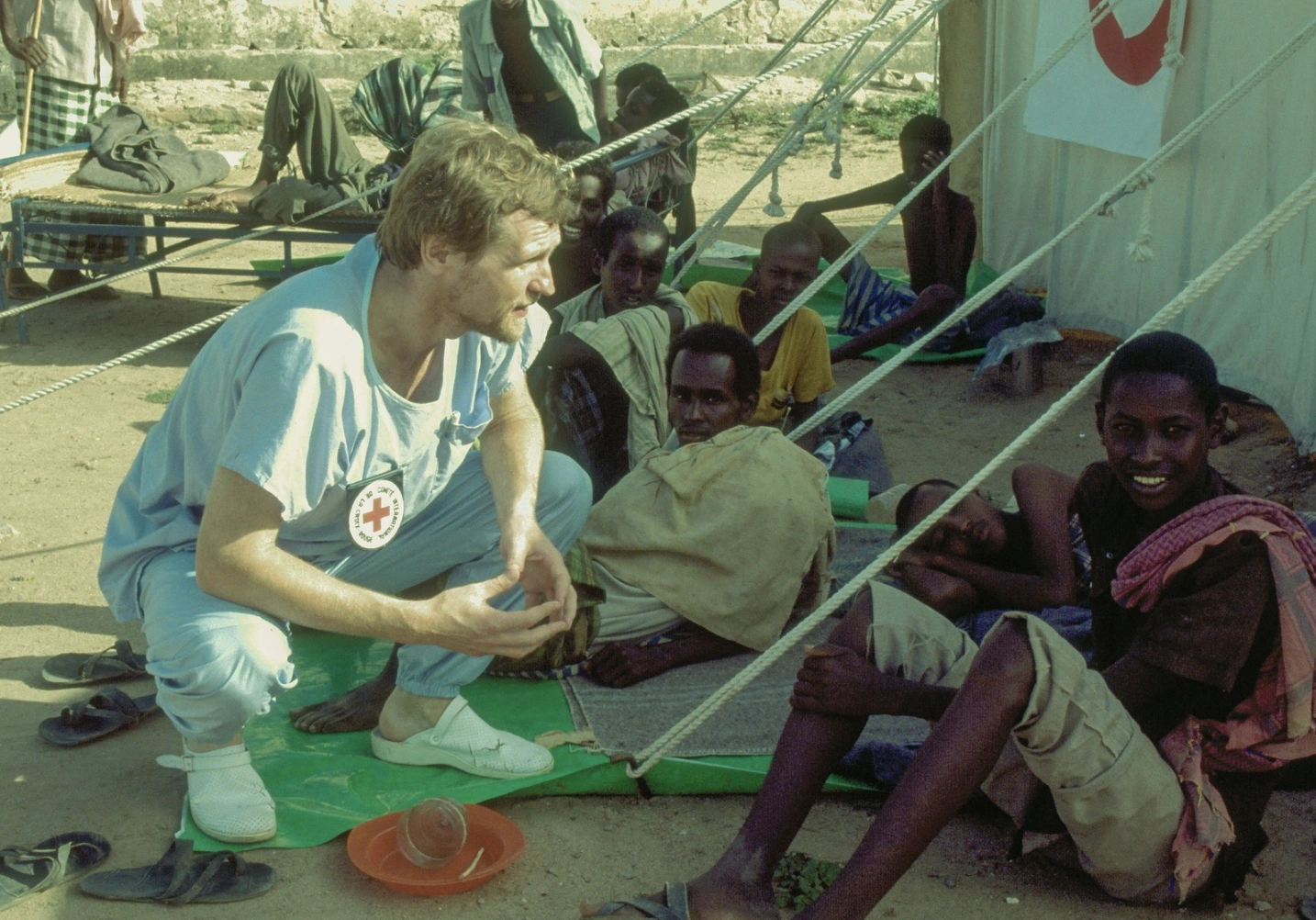

I’ve also written a book about Finnish humanitarian workers, mostly doctors and nurses. Finland is one of the major countries that sends field hospitals to areas hit by natural disasters, like earthquakes in Kashmir or Haiti. I interviewed all the medical professionals and logistics people about why they are as passionate about this work as I am about foreign reporting.They find their work rewarding because they say they gain more benefit from it than they give to the people they help. For them, it’s different from being in a hospital in Finland; they are saving lives with their own hands in the field.

My latest book is about Finnish sailors in foreign ports, especially during the Russian era when we had a strong presence in Alaska and other places. The book also covers interned Finnish sailors during the wars when we were allied with the Germans, and how Finns were detained in prisons in different parts of the world. It delves into pub brawls between Finns and Swedes in San Francisco and even discusses marriages among sailors. It’s a colorful book and quite historical. I even had to hunt for harbor port pubs or bars that are still open.

Interestingly, the most sold book in Finland is my “Reissukirja Travel Book,” where I share more personal stories, especially about my travels. The good thing about this book is that there’s not a single address or telephone number for any hotel or restaurant. It remains evergreen that way. For those writing travel books, my advice is not to include street addresses or telephone numbers, as they can quickly become obsolete.

Have you ever thought of having these Finnish books translated for a bigger market?

I haven’t as they are Finland related and I also think it’s quite expensive to find a market and marketing.

Okay so your new book is not Finland related, the one being published now in August?

Yes, at the end of September, I’m releasing a photo book. This came after I had six or seven photo exhibitions because when you attend such exhibitions, you stand in front of each photo and look into the eyes of the subjects. It makes a big difference, and I hope that impact will be preserved in the book. Many people have told me it would be nice to have a photo book at home. So, finally, the publishing house with which I worked on my previous books agreed that we could produce a photo book, as long as it sells a few thousand copies to ensure we don’t lose money.

What exactly motivated you to write this book at this point in your life? I mean, you could have written such a book 10 or 20 years ago based on your wealth of experience. Why now? Is it because it’s been 50 years, or is the number significant in some way, or is it something else?

Well, I would say age isn’t just a number. If you look at me and consider how much time I have left, that’s a factor. I’ve been so busy lately that I haven’t had time to properly organize my photo library. Last winter, I spent time sorting through tens of thousands, maybe even a hundred thousand photos, to put them in order. I had a great photo editor and graphic designer who made the photos in the book interact in a meaningful way.

Another reason for writing now is a sense of melancholy. After working for more than 50 years, hoping that people read my books and articles and watch my TV programs, it’s disheartening to see the world not moving in the direction I’d like. The tone of the book is not encouraging, but I hope it serves as a wake-up call for people to act before it’s too late. This is about more than just climate change; it’s about global conflict as well.

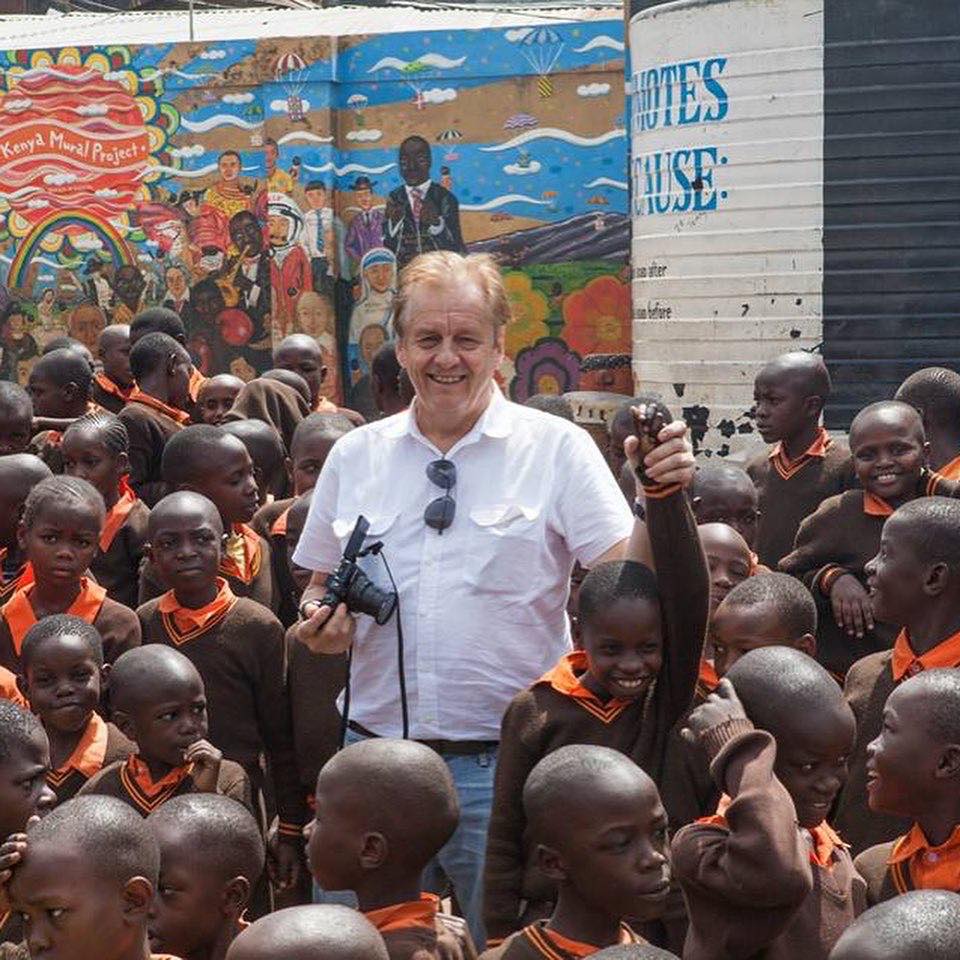

One thing that does bring optimism is the book’s last chapter about education. Despite political promises, education often gets cut. Visiting a local, poor school can make us and the children happy, but it also reminds us of the disparities in education quality. We have to believe in education, whether in Finland or South Sudan, and fight against alternative truths and fake news. Literacy rates have improved compared to 50 years ago, but we still have a long way to go.

In my book, which focuses on developing countries, you won’t find German, American, or Swedish faces. Sometimes I joke that I hate civilized countries because I feel at home among the working class and poor in developing nations. Don’t take it too seriously; it’s not that people in developed countries aren’t friendly.

We’re living in difficult times. It started with the pandemic, followed by Russian aggression in Ukraine, global inflation, and climate change. Extreme poverty is on the rise, more students are dropping out, and the cost of staples like bread and rice is increasing due to various global pressures. We’re also seeing the rise of populist policies worldwide. We’re living in dangerous times, but I like to think that world history has its ups and downs, and we have to believe that we’ll get through this difficult period.

Now, since you have visited countries in the seventies and eighties, and I assume that you’ve visited a very large number of countries two, three, or more times, which countries would you say have changed the most since back then?

I would say, economically, if we’re not talking about politics, China has definitely changed the most since the end of the 1980s. I had a chance to travel by car from Hong Kong to Beijing because there was a Hong Kong-Beijing rally, and one of the famous Finnish race drivers, Ari, invited me to join as press. My Swedish colleagues and I decided to take detours off the rally route to visit villages where the Chinese people had never seen foreigners before. At that time in Beijing, foreigners were only allowed to travel maybe 20 kilometers away from the city. The conditions in the countryside and the poverty in China were eye-opening. I’ve returned to China many times since then, and the economic growth is amazing, although the political situation is different.

In contrast, North Korea hasn’t changed much except for the development of more dangerous ballistic missiles and weapons. People are still suffering in the countryside, and there’s no personal freedom. In other countries like Kenya, the changes are most noticeable in big cities like Nairobi, but unfortunately, many countries have seen the clock turn back in the countryside. However, the advent of the Internet and mobile phones has made a big difference in material wealth. At the same time, the gap between rich and poor has been growing in every country.

So is there anything left on your bucket list? A place you haven’t been to that you would really still, you know, love to visit?

When I finished my travel book, I expressed a wish to visit St. Helena Island in the South Atlantic. At that time, I was so engrossed in my work that I couldn’t spare the time for a ship journey from either Southampton or Cape Town to reach the island. However, just before the pandemic, while I was in South Africa for a story, I discovered there were now bi-weekly flights to St. Helena.

Having previously gathered ample information about the island, I decided to cover a story that surprised many Finns: Finnish prisoners of war were once held on St. Helena by the English. Some of them had met their end on that faraway island. I even visited their gravesites, placing small bottles of a famous Finnish brandy on their resting places as a tribute. The question arose: why were Finnish prisoners of war in St. Helena? The answer lies in history. They had participated in the Boer War at the turn of the 20th century, siding against the British. After the war, several thousand prisoners, including Finns, were transported to St. Helena. The letters of one such prisoner have been preserved, providing invaluable historical insight.

My visit to St. Helena was eventful, from covering the Finnish prisoners’ story to visiting Napoleon’s residence and his then gravesite. Having ticked that off my list, I don’t have a burning desire to visit other remote places just for the sake of it. Some destinations beckon a return visit, especially those with people and stories that have deeply impacted me, like Afghanistan, where I’ve been 13 times.

That said, the idea of visiting a newly independent nation does intrigue me. Whether it’s Catalonia, Scotland, or New Caledonia – all places I’ve been to – I’d like to cover their independence celebrations and not just visit for the novelty. Technically, Bougainville might become independent around 2027. If it does, and I’m still around, I’d love to visit. I’ve been to Papua New Guinea twice, and have contacts in Port Moresby who could assist with the story.

Alright, Rauli, as we conclude our interviews, we always like to ask the same intriguing question. If you could invite any four people, from any era in human history, to an imaginary dinner, who would you choose as your four guests and why?

Yeah, I’ve been thinking about this. Some people might want to invite Mao, Stalin, Napoleon, Caesar—figures like that. But that’s not really my focus. I have two sets of guests in mind. The first set would include Nelson Mandela, Muhammad Ali, Kofi Annan, and Barack Obama.

But honestly, what I’d really like is to invite four people — musicians and journalists — who are in Afghanistan right now and looking for ways to get out. If this dinner could get them out of Afghanistan, I’d be more than happy.