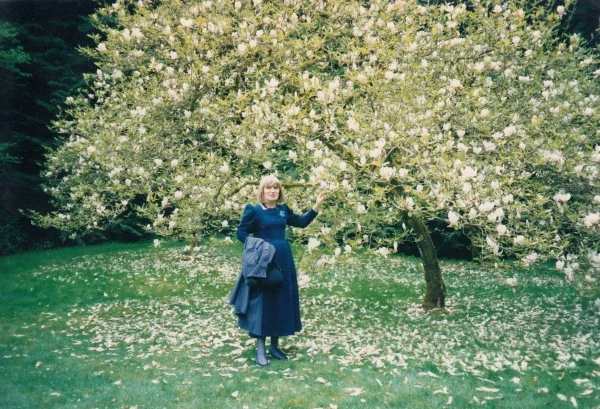

We end the year presenting a truly incredible traveller. Born at the very end of the 1940s and growing up in the UK, we believe Lily Marie West to be the biggest female British traveller. Settled in Japan since the 1970s, she has been to every country in the world – and verified for this by us – and is still at it, though still very much settled in Japan. Lily opted to show us photos of her life in Japan rather than her endless travels and we are exceptionally pleased to be going on this voyage with her.

Lily, tell us something about your early life and how your love for travel developed.

My father was a British soldier who met my German mother after the war. I was born in Germany, but did all of my schooling in the UK. However, we visited my German grandparents every year, which meant I was brought up bilingual. My grandfather was an avid stamp collector, but I was more fascinated by the names of the countries at the top of the pages of his albums than by the stamps.

I just wanted to go to all of them! This desire never waned, but just increased in strength as I grew into my teens, so I specialised in foreign languages with this obsession in mind. But I always felt myself to be caught in a kind of dichotomy: I yearned for adventure and simultaneously I wanted a quiet domestic life. I’m glad that I managed both in my life!

What type of traveller do your consider yourself?

I was definitely an overland traveller. Planes were still rare in the late 60s and early 70s. Even while I was at university, I went overland to India and back on local buses and trains. Finally, when I graduated, I set off for India again with the intention of never returning to the UK. After I became gainfully employed in the 80s, my style of travelling had to change and focused on 3-month summer trips every year with a lot of flying. In the 90s I did several African overland truck trips and after that, I concentrated on getting to the places I had missed, not always easy given the visa problems, but when there were about ten countries remaining, I was determined to make it. I was never interested in just putting my feet over the border; I wanted to see the countries, even if it meant returning many times, but I never had the money for luxury travel. Not sure if I wish I had had; I think the way I travelled meant I experienced far more than if I had been staying in Hiltons.

You are from the UK but have lived in Japan for many years. To what extent do you believe that your country of origin has influenced who you are and your perception of the world?

Well, the UK gave me the English language and a good education, which came in handy when I had to settle down and work, which I did when I became 30. It also gave me my sense of humour, which I’m sure has helped to keep me going through various dodgy travel situations. You don’t lose your country of origin: though I have lived in Japan for well over 40 years, I don’t feel Japanese, but I do know how to live here. Every time I return to Britain, I realise that things have changed so much that it is now a foreign country for me..

And what aspects of Japan were hard to adapt to initially given you are an outsider?

Speaking Japanese came fairly quickly, but I had to learn to read and write, which took much longer. Then I also had to deal with a very different mindset when I started working in Japan! Things had to be done the Japanese way, which often was not my way, but I had to learn to adjust. I also had to accept that no matter how long I had been in Japan or how well I spoke the language, I would perpetually be an outsider.

Until I got used to it, I found the separation of genders difficult. As a woman in Japan, you generally do not have male friends like you would in the UK, but then I grew to greatly prefer the company and friendship of Japanese females. I found that for most Japanese men, I would always be a foreigner first, whereas for most Japanese women, I would always be Lily, a fellow female, first. Easy to say which one I prefer!

You are now one of the few women to have been to every country in the world. Why do you think men are so much more ‘ahead’ compared to women in terms of this achievement, and what does it mean to you to be the first woman from England – that we know of – to do this?

Probably (and sadly) the feeling of greater personal safety would be the main reason for fewer women achieving this goal. In this respect, after a bad experience in 1996 in the Central African Republic where I was held hostage by soldiers from the losing side in a civil war for two weeks before escaping, I decided to hire armed bodyguards for travelling around Somalia and Nigeria. Lucky I did that, because I was held up by Nigerian bandits, who opened fire at my vehicle. My bodyguards shot two of them. Naturally I gave them a larger tip!

If I really am the first Englishwoman to visit every country in the world, I am very proud of this! But it was not my intention to break any record; I just wanted to go to the places.

Of the countries you visited, which one surprised you most, positively and negatively?

Surprised me? Well, I became obsessed with India, visiting 7 times for a total of 2 years there. There was just so much to do and see, but I wasn’t surprised because that was what I was expecting.

I think it would have to be Madagascar, since I had no prior expectations. Jungle, hill towns and desert all on the same island. Then there was the amazing Fawlty Towers of Madagascar, the hotel in Morondava! Negatively, while Japan surprised me with its urban ugliness when I first arrived, it would have to be China in 1985. I had enjoyed my first visit in 1982, but in the intervening three years, people had changed to become greedy and manipulative. It was as though they enjoyed being as awkward and dishonest as they could. Western money had arrived and this was the consequence. It was the only trip I have ever cut short and returned home!

Tell us a couple of travel stories, which have really stuck in your mind.

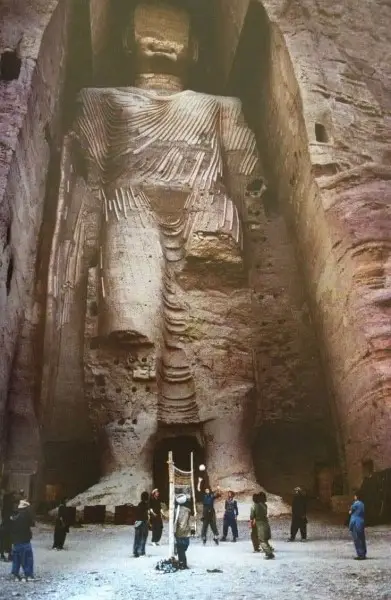

The first story is about a place, which sadly no longer exists. I count myself very fortunate to have seen it!

The bus to Bamiyan was already crowded; Afghans had taken most of the space inside, and when we tried to get in, they made us clamber up on to the roof. “Better here,” said my American friend, Ed, “we’ll get the views.” True enough, but, as our feet dangled over the edge of the bus, we also got the wind, the dust and at first the cold, then as the day progressed, the heat. But what an adventure, we thought, as we drove through the desert-like landscape.

We made several tea stops, and it was at one of them that Ed’s stomach made such a strong protest, that he raced up a slope to squat behind some rocks. Unfortunately, some small children followed him and amused themselves by throwing stones at him, one rather accurately, which caused him to yell. I heard this and scattered the children with help, enabling Ed to finish his business. Gesturing that he had an upset stomach, he tried to get inside the bus and may have succeeded, but at that moment a stone hit him in the back and he gave chase to the perpetrator. He caught the child by the scruff of the neck and started to administer summary justice, when a significant number of what appeared to be the boy’s male relatives arrived on the scene. Ed attempted to reason with them, but as he did, the boy bit him and escaped his clutches. The bus driver, sensing trouble, decided to drive off and only thanks to a truly valiant run did Ed manage to jump on the back of the bus and haul himself up to the roof. The much larger farewell stones fortunately missed their target.

On to the Bamiyan Buddhas! By the time we reached the surprising green fields of the valley of Bamiyan, dusk was approaching the red cliffs with the giant standing Buddha statues. Their faces had been hacked off by iconoclastic Muslims centuries before, but the 180-foot height of the tallest one was stupendous as it dominated the small dusty village from its carved position in the cliff face.

Both Ed and I wanted to see the statue before it grew dark, so we left our bags in a teashop and set off. We spotted a set of roughly hewn steps and were just about to start climbing when a ragged Afghan soldier stepped in front and pointing his rifle at us, made signs to indicate that it was too late and entry to the staircase was closed. Pretending to be disappointed, we started to move away, but as soon as the soldier turned his back, we raced past him and began to climb the steps. After all, I thought, we had come all this way to see the Bamiyan Buddha and did not intend to be turned back just when we had got there. We could hear the angry shouts of the soldier for a while, but were concentrating on climbing the steps, which were in parts so crumbly as to be perilous. But they were nothing compared to the danger with which we were confronted when we reached the Buddha’s face.

To get a better view of the stunning frescoes, we had to jump over a gap in the rocks. We did it without pausing to think, but a misjudgement would have been the end of us. But what a sight! The sun was coming down, so we realised that we had to use what daylight there was left to us to descend safely. Slowly we made our way down to the bottom of the steps, where we found the soldier waiting for us.

Undeniably infuriated, he had fixed his bayonet to his rifle which he now stuck in our faces and babbled incomprehensibly in Farsi at us, thrusting the bayonet closer to try to frighten us. Ed took charge of the situation and made it clear to the soldier that we did not understand him. The soldier then searched his brain to try to get his point across in his extremely limited English. “Afghan good! Tourist no good!” he stated. He could see that we had understood him and a flicker of triumph crossed his face before Ed replied: “Tourist dollar! Afghan no dollar!” Mortification instantly replaced the earlier triumph. The soldier’s mouth was open but he had no riposte. Slack jawed, he lowered his rifle, at which Ed and I set off for the village to find somewhere to sleep.

Fifty years ago on a solo trip around India. I wonder if this India still exists! It does in my mind at least.

At one stop between Kotihar and Siliguri a bedraggled beggar crawled under my seat to get some sleep. Nothing unusual about that on a third-class Indian train, but a little later a uniformed soldier got on dragging a large tin trunk, which he wanted to put under the seat. He prodded the beggar with his boot to get him out of the way, but the beggar did not move, so he kicked him. There was still no sign of movement, so the soldier reached under the seat and dragged the beggar out. It turned out that there was a good reason why he had not moved. He was dead. He had died under my seat without making a sound! So now one would imagine that the soldier would be in a bit of a quandary as to what to do with the corpse. But he was not. The soldier spoke with one of the passengers who grabbed the spindly legs of the beggar, while he himself took his arms. Together they hauled the beggar out into the corridor, made their way to the door and waited until the train passed over a river. Then they heaved the dead man out of the opened door and he fell into the water with a gigantic splash. The soldier came back into the compartment, pushed his trunk under the seat and took out his newspaper as if nothing untoward had happened. My mind had retreated to a state of disbelief regarding what I had just witnessed. A Sikh stretched out on the luggage rack could see my shock, which he shared. He propped himself up on his elbow and called down to me: “I too am a stranger in this strange country!”

How has travel changed from when you began going around the world to today?

There are so many dissimilarities between travel today and travel then back in the late 60s and 70s. Of course there were no guidebooks or computers from which to get information, and naturally there was no Internet or email. We had to collect letters sent to us at the Post Office. Prebooking a hotel would never have occurred to us. There were no mobile phones with which to call your parents or friends back at home. In fact if you had to make an international phone call from the main telephone office in New Delhi, it would take a wait of several hours before you were connected, the line would be terrible and the cost sky-high.

Few travellers had cameras, certainly not the digital variety which appeared later. I did have a camera, but it was broken and I only brought it to sell in India. There were no MP3 players and basically no music. There were no credit cards to fall back upon if you ran out of money. Your problems were yours to solve. English had not yet become the de facto global language of the world. For purposes of communication, it was often still necessary to be able to speak French or German too.

There were no “adventure” travel companies like Explore and Exodus. You had to do things under your own steam. Few people took planes; trains, buses and boats were the major methods of travel. Perceived physical safety was greater; hitchhiking was common, for though lack of imagination was a reason not to travel, lack of money was not. The hippies just went anyway. I know I did. In the words of that era: we turned on, tuned in and dropped out.

From what I have experienced, today’s backpackers differ in that respect. They do have money, they fly everywhere, many have what is now called a gap year after which they return home to a waiting job. When we left, we had no job waiting for us. This is not to decry them, for the times have changed. I do feel however that the backpackers have no ideology. The hippies did.

For them, society was perhaps over-simplistically divided into “straights” and “heads”, and you were treated accordingly, depending on which group you were identified as being in. They had developed a counter-culture, which regrettably was watered down to make it suitable for mainstream consumption. The idea of Istanbul and Kathmandu becoming the venue for package tourists, as much as they have, would have been unimaginable. When you finally reached Kathmandu after the long overland journey from Istanbul, you felt that you had accomplished something special. In Kipling’s words, which were still true then: “The wildest dreams of Kew are the facts of Kathmandu.” Sadly, not so now.

What can you never travel without?

It used to be books, but now it would be my tablet! The wonders of modern technology do amaze me. Moreover, in the last thirty years or so, following a Japanese custom, I have always brought an apron with me! If I am invited to stay with someone, I love to cook or just help in the kitchen (a brief return to domesticity maybe?), but I wanted to try to keep my few clothes clean for as long as possible, so my apron has proved very useful. Plus, not only for windy days, but also to blend in more in certain countries, a headscarf!

How have your family and friends taken your exploits?

My first trip alone was hitchhiking to Spain when I was 17. My parents were furious, because I had told them I was visiting a friend in London! I left home straight after school and had a government grant see me through university. They were completely against my travels at first, but when I visited my final UN country in 2016, my father did tell me how proud he was that I had hung in there and fulfilled my childhood dream.

Can you give us some Japan gems that not many outsiders would know?

I would recommend the outlying islands, especially the Ogasawara Islands, 24 hours by boat from Tokyo. It is a different world down there. Of course Hokkaido’s northernmost islands of Rebun and Rishiri. And I must not forget the town of Kamakura, where I live. It is worth so much more than the usual daytrip from Tokyo!

So now that you have completed all the countries of the world, what is next? Do you still travel a lot?

Of course Covid-19 has put a stop to any travel from Japan, but strangely I have got used to being at home. I think this is because I am satisfied that I have achieved my goal. I had hoped to get to my remaining unvisited territories (Pitcairn, Tokelau, Tristan da Cunha, BIOT and Abkhazia), but I do feel I have done enough. I survived two bad car accidents in the last three years, so maybe this is a sign telling me that it is time to enjoy a more stay-at-home life!

Moreover, I would like to write more! But I’m still trying to find a publisher for my first travel book; 400 pages long about the people I met on an overland trip to India in the early 70s. Any help to find a publisher would be much appreciated!

Finally, our signature question – if you could invite any four people from any period of human history to dinner, who would you invite and why?

Isabella Bird, the British explorer, who travelled in Hokkaido in the 1880s. I would love to hear about her adventures then!

Iso Mutsu, a British woman, who lived in Kamakura from 1910 to 1930: I do wonder what Kamakura, my home for nearly 40 years, was like then!

Alexandra David-Néel, the explorer.

Can I have a fictional character? If so, I would choose Anne of Green Gables, the heroine of my favourite book as a child!