Jacquelyn Kunz, an amazing and daring traveller, became the first known woman to travel independently to Afghanistan after the Taliban takeover. She is always pushing her own limits as well as those of the travel community, often travelling overland by public transport as a solo female.

She has called Sudan home for the last eight years, during which time she has witnessed two coups and the Sudanese revolution. Jacquelyn frequently travelled through the Kordoufan and Darfur regions of the country, knows Sudan very well and is currently participating in relief efforts to help people who are suffering because of the current war which recently engulfed the country.

At the time of publishing this interview, Jacquelyn was at the Egypt-Sudan border. We decided to interview her in order to better understand the current crisis in Sudan as well as to get recommendations what everyone in the NomadMania community can do now to help local people and participate in a good cause.

This interview is available in video form on our Youtube channel …

and text (read below) …

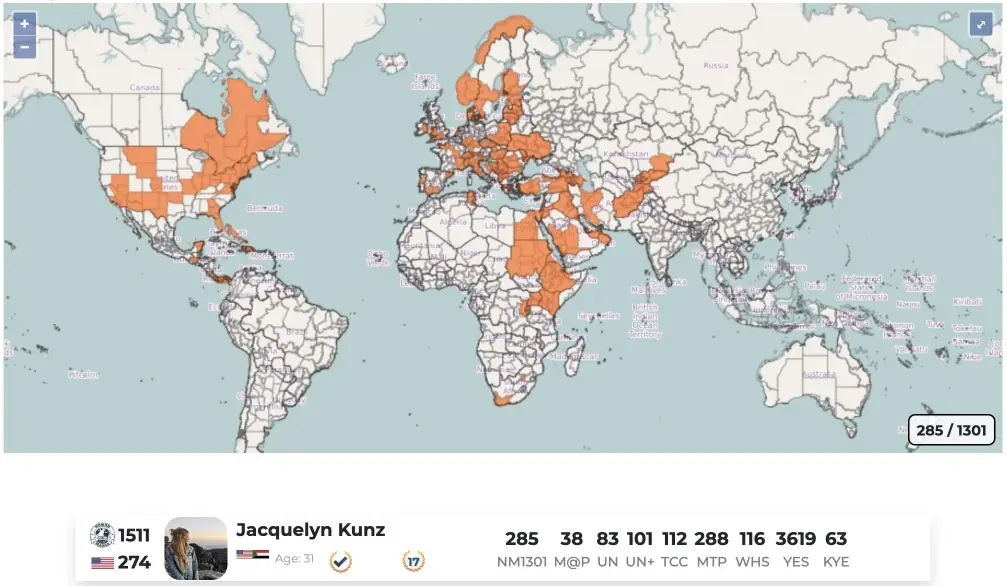

Jackie, looking at your NomadMania profile, I have noticed that you are really well-travelled in places that most people don’t usually start from. I’m talking about the Middle East, Afghanistan, and all NomadMania regions in Iraq.

This is pretty extraordinary. So what made you start travelling from those particular places? And can you tell us maybe about your travel background to have a better picture of who are you as the person, beyond this mysterious traveller?

Okay, hard question. Yeah. So actually, I believe Sudan was the 8th country that I visited, and Eritrea was actually my 9th. So I kind of started in a weird order where some of the countries that people might leave for last interested me the most.

But when I started travelling, I didn’t really have those 193, 195, and 197 goals in mind. I was just looking for places that interested me. I grew up in a small village in upstate New York, but we were really close to a city called Utica, which is known for taking in a lot of refugees. I was exposed to a lot of people coming from Syria, Iraq and Somalia as I was growing up. So knowing these people and hearing stories of these places, I had always wanted to be able to see them someday. I studied Arabic as well at university for a little while. So that really piqued my interest specifically for Arab countries in the Middle East.

So, I thought I could really understand them more in-depth, being able to communicate in the language a bit better than I could in some other places. That’s what made me visit Sudan, Iraq, and then even Afghanistan last year.

Was it like, only travelling, or you were trying to combine your profession, relying on these skills that basically made you more welcome in those places?

That’s actually a newer thing I’m trying to do. I work in education development, and I’ve been focused on Sudan and Egypt, and I’ve done a little bit of work through COVID with Yemen and some other countries across North Africa and the Sahel, but I’ve always been based in Sudan. But with my trip to Afghanistan last year and hearing everything that’s happening with women’s education there, it’s kind of become something I want to combine more with travel. I do have this skill that I could use in places that might not have access to it.

Right now I’m trying to look for ways to combine travel with expanding education access, teacher training, and syllabus design in some of these places, so hopefully in the future, that becomes a more integrated aspect of my life.

Can you explain this type of education a little further? What does it mean precisely?

I’m an education specialist, so I work in curriculum design primarily, and then teacher training and low-resource contexts. I write basic children’s books to be used in schools, and then I work with teachers on how to deliver these lessons in a way that gets the information across, but in a situation where they don’t have any kind of electronics, or maybe they don’t even have a chalkboard, or maybe they don’t even have books themselves.

And then I work with teachers on how they can become effective, rather than just delivering a lesson to students, ticking the box, saying, okay, this is done, how they can actually make it impactful in a way that the students actually walk away with having learned something.

How did you stumble upon NomadMania? What attracted you to our platform and our project in general?

Actually, it was kind of by chance. I was in Socotra I guess two years ago now, and people were talking about NomadMania, and I had never heard of NomadMania before. Like, what is this? And then everyone’s like, oh, yeah, it’s this website. It shows you your ranking and it shows the regions. So I really like that aspect. Thanks. I’ve met a lot of country counters over the years that just go to capital cities, tick them off, and then move on. But NomadMania, with its division into regions, encourages people to see more of a country.

And I always used it now for trip planning. So if I’m going to a country, like when I was going to Iraq, I was looking at the different regions and like, okay, what are the cities in each region? What are the different experiences? Museums, what not? And I really like the Dark Side and the Bizarrium (Series), so I always take a look at what there is there. I found some weird stuff through that already.

You told us that you have lived in Sudan for the last eight years. How did life in Sudan look like for those people who probably didn’t hear much about this country, who maybe generalise around Africa as a whole? Can you describe Sudan as a whole (before the war)?

I love Sudan, and I think everyone that’s actually been to Sudan often sees it on their Instagram stories or Facebook posts or trip reports. And they comment how they were just in awe of how friendly and generous the people are. Everybody wants to invite you to their home. Everybody’s offering you food. Travellers that come during Ramadan are stopped at the time of Iftar and just offered free plates of food in the street.

That’s one of the reasons that I’ve stayed for so long going there. I felt at home immediately because people are just so welcoming. They open their homes to you. You become instant friends with people that come from such different backgrounds, and you can really connect with people on just a human level.So it’s a way of life that emphasizes family and friendships more than working yourself to death. So coming from the US, I found that to be extremely refreshing. Whereas in the U.S., your job is kind of your entire life, and you fill in your free time by getting tasks done at home, in Sudan, if you run into a friend on the way to work that you haven’t seen in a few weeks and you stop to have a coffee, your boss understands, you just say, oh, I ran into a friend. And they’re like, oh, okay how were they?

So it’s just a very different aspect, or it’s a very different approach to living, which you can see even now with how people have come together from the diaspora, from within the country, just trying to help each other. So even in tough times and times of war, the Sudanese spirit is just so, so strong. And it’s just really refreshing to see that it’s withstanding this.

Would you consider these warm feelings between people and everything you described just now is a special feature of Sudan or the entire region of northeastern Africa?

You obviously get that in other places as well. I only can speak from the Sudanese context because that’s the one that I know in depth. But I’ve spent a lot of time in Ethiopia as well. I’ve spent a lot of time in Egypt as well. And you do see that there. I think part of it as well, though, is that Sudan doesn’t see the tourism that some of the neighbouring countries have.

So they also don’t have that idea that foreigners are there and they have a lot of money and that kind of thing. In Sudan, people still see a foreigner coming through as a guest, and they want to show them the best of the country, especially because the media does tend to show maybe the darker side a little bit.

So could you please explain to us more in depth what the background of the current war is, what were the first things that led to this, and what is actually happening in the country now?

Everybody’s heard about the genocide in Darfur from the early 2000s. Janjaweed were the perpetrators of this genocide. Throughout the years, they’ve been legitimised and rebranded by the Sudanese government, and they’re now known as the RSF. They stayed in Darfur until 2019 when the revolution started.

There was a popular uprising amongst mostly college students, different women’s groups, doctors and professionals in Sudan that came together, formed mass protests and a sit-in, and then eventually took down the dictator. But during this time, the dictator had brought in the RSF, who used to be the Janjaweed from Darfur, to help suppress these protests. By the time the dictator fell, you had this group of paramilitary militia that come from Darfur and you had the actual army.

To prevent it from becoming a civil war between these two groups at the time, they decided to do a power-sharing agreement. And since then, the two groups have been ruling the country, but they’ve been talking about integrating into one unified armed force. Obviously, nobody likes that. So the RSF is more of a family business. They’re loyal to their leader. Their leader is very wealthy from having lots of gold, so they’re there for the money, whereas the army is more loyal with nationalism to the country. Recently they’re not coming out and saying exactly who started it, but what the belief is, is that the RSF was trying to stage a coup of sorts and take over the country and become the sole leaders of the country. They started attacking the airports.

I know a lot of people probably have seen the scenes that came out of Khartoum International Airport a couple of weeks ago and some of the other air bases that the army held in the north near Merowe and Karima, where some people might have visited the pyramids in the mountains, and then also in Darfur. One of the advantages that the army has over this paramilitary group is air defence. So that was the paramilitaries’ attempt to quell the air defence tactics that the army would have had.

Well, it didn’t work. So now here we are in the third/fourth week of fighting, which is mainly happening in Khartoum, in residential areas. A lot of people are stuck, essentially within their neighbourhoods. They can’t get out because there’s shelling, there’s missiles, there’s street fighting, there’s bullets flying everywhere. It’s a war between two generals that ends up having millions of civilians caught in the middle.

And the civilians have no stake in this war. We don’t want either side to be in charge. People have been fighting for civilian government, they’ve been fighting for democracy. And now they’re dying because two generals both want to be in charge and are fighting each other for it.

What can the rest of the world do in this situation when you have this kind of internal conflict?

Some of the things that people are asking for, one of the big issues, is that most hospitals in the country are closed.

Over 70% of the hospitals have closed for either lack of supplies, lack of doctors, or they’ve been bombed. So there are a few groups, like the Sudanese American Physicians Association, that have been able to get money and supplies into the country, and they’re running makeshift hospitals in abandoned gynaecology wards etc. that they’ve been able to set up securely. They’ve been doing a lot of fundraising for medical relief.

Some of the other issues that we’re having are regarding sanctions on the country. There are many people that have families that are very willing to send them money to help them get out of the country with the exorbitant prices of bus tickets. But because of sanctions, money can’t get into the country. People are stuck without a way out, essentially. So, people are asking to put pressure; if you come from a Western government, you can write to a representative, representatives put pressure on them to help, support some kind of ceasefire agreement and take dual citizens.

A lot of the countries are evacuating, but they’re leaving the dual citizens behind. I know I come from the U.S. And they say we have 16,000 Americans in the country, but the majority are dual citizens. And the U.S. has completely pulled out and left them behind. And nobody is pressuring the U.S. government to come back and help them. Or to run more evacuation flights. They took their embassy staff and they left. And a lot of Western governments have done the exact same thing. Some have shredded passports that were within their care. I know the French embassy specifically had a lot of Sudanese passports for visa processing, and when they left, they shredded them.

We have these people who are stuck in the country with no money, they don’t have a passport, and some dual citizens for whom there’s no way to get out. So a lot of people are just asking to raise awareness that this is happening, putting pressure on Western governments to do something to help.

The UN has not set up any kind of aid around the borders. I went to the border myself a few days ago. I was picking up some of my neighbours that were coming from Khartoum, and there was nothing there. There’s no shade for people to rest in. It’s 110 degrees Fahrenheit, over 40 degrees Celsius. There’s no food, there’s no water. We brought about maybe ten to 15 litres of water with us. It was gone immediately because the second people saw that we had water, it was just gone.

People are desperate, and there’s nobody down there helping. The only help that’s coming through right now is from Sudanese aid groups. Or people in the diaspora that have flown here to try and get things in. Meanwhile, we have a war in our country. We’re all very concerned about friends and family we’ve lost contact with, and we’re trying to get to the grassroots, organize to save people.

Even for me it was shocking, because for the UN workers that were stranded, it was the Sudanese who were the ones mobilizing to volunteer to help get them out. And then where’s the UN helping their own people or helping the Sudanese people? It’s a very frustrating situation.

Anything else you would like to add here, like what else the NomadMania community or other people can do in order to participate to do some good in this situation?

I think one of the things is, a lot of the nomads, the community, have visited Sudan in the past. I think if people are deciding to share photos or stories from their trip, please include something about what’s happening now. Don’t just use Sudan at the moment for likes or for clickbait. Include a resource or say, hey, this is a great account to follow if you want to see what’s going on or put up a fundraiser, something like that. Don’t make it about you and your trip right now. This is what we can do now as travellers to repay that kindness to this country.

What are your plans? Like, you are now at the border and what are you planning to do starting from this point? How long are you going to hang out there? Are you going to maybe formalise activities there because there is so much work to be done and you are definitely in the situation where you can be the bridge between Sudan and the rest of the world?

What I’ve been doing since I got here is I’ve been making contacts and going around talking to people who have maybe empty apartments or people that have an Airbnb, different things like that, and just setting up places for families that get here, for a place to stay, to rest before they move on to Cairo or figure out their next step. Because of the border, the wait time is between four and five days.

People have no idea when they’re going to get through, when they get here they’ve often never been here before, and they have no idea what’s next. So I’m helping set up a kind of established network, apartments and places that they can stay for a couple of days to regroup, to rest, to gather themselves again before they figure out what’s next. I’m also doing a lot of passing messages around.

A lot of the work that we’re doing at the moment is connecting people around. Issues such as medicines or about buses, transport or if an area is safe. A lot of this is going through the diaspora. So I might know somebody that has asked me a question and then I put it out there and then I get back to them. It’s a lot of networking, putting people in contact that need something, somebody outside.

In every NomadMania interview we usually have a signature question. I understand it doesn’t really relate to your particular situation right now, but this is something we can dream about… If you could invite three or four personalities, with whom would you like to have a dinner, if you could?

There are two that really inspired me to travel. When I was a kid, I read ‘From Beirut to Jerusalem’ by Thomas Friedman, and that was one of the first things I read. They’re like, I want this life. I want to get out there. I want to see things, and experience things. So definitely Thomas Friedman, really, even just to thank him for the inspiration.

Anthony Bourdain, of course, was a huge influence of mine. I remember the episode when he went on the Congo River. I think that was in 2013 when the episode came out. And then that’s what really set my sights on Africa. I was like, this, I want this. It would have been very nice to have met Anthony Bourdain. I actually went to college in the same city that he went to college in, so I always kind of had that connection.

And I’m a big fan of Haile Selassie, the Emperor of Ethiopia. I’d kind of like to meet him just because I was a big fan.

Initiatives which support the people of Sudan

Probably the best online resource run by the diaspora with up-to-date info, real ways to help, background on the conflict and templates for writing to representatives.

2) Fundraisers for medical aid:

You can donate through the websites and it also includes info about the hospitals they are running in Sudan.

3) Sudan Relief by Mazin Bashir Fund

Usually, I wouldn’t share a gofundme because people get iffy about where the funds go, but this one has been posting about fund usage very transparently and is very trusted.

Follow Jacquelyn on her instagram and see more of her updates about the crisis in Sudan.